Nearly a

century of change has created a more flammable forest

Back

|

1909 |

1948 |

|

|

|

1958 |

1968 |

|

|

|

1979 |

1989 |

|

|

-Photos courtesy of U.S. Forest Service

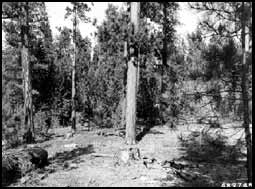

In 1909, the U.S. Forest Service sent a photographer from its

Forest Service photographer K.D. Swan returned to the site in 1925, hoping to document the after-effects of the logging. He repeated the process in 1925, 1927, 1937 and 1938. Then others took over the task, returning time and again to the same photo point.

The Lick Creek photographs now show how logging and the exclusion of fire

changed one

Once a moderately spaced, fire-resistant forest of uneven-aged ponderosa

pines, Lick Creek became a fire-prone thicket where the pines competed with

shade-tolerant

Prior to the advent of wildland firefighting in the early 1900s, surface fires burned through the lower elevation forests of the Bitterroot Valley at intervals of between three and 30 years, killing the smallest trees but causing little damage (other than fire scars) to the larger pines.

At Lick Creek, one pine stump showed 16 fire scars between 1600 and 1895, an

average fire interval of seven years. Scientists and land managers now believe

that both the start-of-the-century timber sale and the subsequent lack of fire

contributed to the changes at Lick Creek. Logging scraped off the surface

vegetation and pine needle litter, exposing mineral soil. Several of the large

pines left after logging died from windthrow or from mountain pine beetle

attacks. The most heavily logged stands eventually grew thick with tall shrubs

and

Lick Creek is not an anomaly. There are 40 million acres of ailing ponderosa

pine forests in the western