Chapter One

Pemberton Historical Park: A Monument to the Past, A Reflection of the Present

Andrew Stuhl

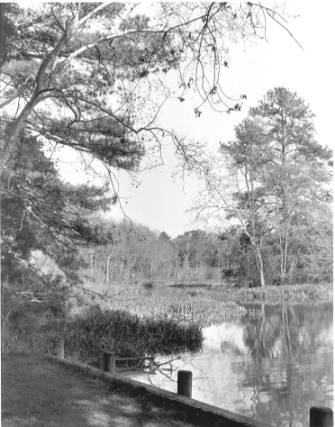

View

from wharf landing at Pemberton Historical Park.

Photo courtesy of Nicole Brown

The

speed limit on Plantation Lane is a comfortable 10 miles an hour, which both

protects the shocks on your car and allows you to take in a full view of Pemberton Historical Park.

In the driver’s seat, I watch as the park opens up before me,

inviting me to relax and stay awhile. As

I allow my SUV to manage the bumps and dips of the old dirt road, I drift

further and further from the present day and into the world of the 18th

century.

I

have come here not to simply enjoy the aesthetic beauty of Pemberton, but also

to discover what lies behind that beauty.

I have been drawn to the park by the intrigue of the rich history that

whispers through the wind-blown trees and creaking floorboards of Pemberton

Hall. I want to develop a

connection to that history. I

want to develop a relationship with the people who not only settled and

developed this land hundreds of years ago, but also those who conserved it,

preserved it, and restored this land less than fifty years ago.

I want to learn what they did here and why, how they valued the land on

which they lived, and how those values changed the land and river they called

home. I want to appreciate their

lives and what they lived for so that I can better appreciate why the land,

people, and Wicomico River are what they are today.

My

first step is to meet with Bill Wilson and tour the park.

Bill is the current president of the Pemberton Hall Foundation, which

was formed in 1963 to restore Pemberton Hall and the land surrounding it in

hopes of creating a historical education center. Bill lives and breathes the history of this area.

Not only did he co-chair the creation of the Foundation, but he’s

also put in almost 5,000 hours of volunteer service over his 28-year career

here. And when Bill says “volunteer

service,” he really means investing in incredibly detailed research,

drafting and putting in effect hand-blistering construction projects, and

fighting tooth and nail to protect his work from hungry developers.

All of this has left him with a wealth of knowledge eager to be

dispensed to anyone willing and interested.

I grab my pen and paper, do a few hand stretches, and am on my way up

the oyster shell walkway to Pemberton Hall.

Bill greets me in the front yard with a firm handshake and a smile,

wearing an unlabeled navy blue and tan cap and a gray Mary

Washington College Sweater. We

exchange pleasantries before starting on our tour.

We keep it curt; we both know that there is a lot to talk and walk

about.

A chilly breeze has picked up even though the sun shines intensely.

We begin on the southwest side of Pemberton Hall facing the Wicomico

River, the wide-bodied waterway that connects Pemberton to the mercantile

capital of the Eastern Shore, Salisbury.

If it weren't for a wall of trees erected on the banks, I would have a

clear view of the water from here. Instead,

I'll have to settle for the glimpses that escape through the cracks of the

hanging branches. Plantation

Lane cuts across my view forming a nice off-white border for a postcard-worthy

landscape. A mature oak

tree stands to my left in front of the building, casting shadows on two cozy

looking benches. Behind us, the

open and empty farmland can be seen past Pemberton Hall, stretching along the

horizon and creating a stark contrast with the rows of trees on either side. Meanwhile, unfinished worm fences slither around the house,

forming a partially enclosed play area for the front yard.

And, I must say, the yard is holding on strong for late winter.

There are some scattered patches of browning grass, but, for the most

part, it is mostly a green pattern.

Bill’s voice fades in faintly, “Let’s go down to the river.” He is already two steps ahead of me by the time my brain

processes his words.

“Sounds great,” I say. My

voice has traces of nervousness, but it is mostly filled with anticipation.

We make our way down a slight embankment beyond the road to the

secluded path that hugs the coast of Bell Creek.

Guarded by the canopy of the trees above, the trail makes for a perfect

escape from the bright sunlight. As

my eyes adjust to the dimness, the rich green color of the Holly leaves

surrounds me and the ground below becomes softer, my foot leaving prints in

the mixture of fallen leaves and twigs. Up ahead, a cleared landing awaits us. Bill strides ahead of me, obviously excited.

We reach the landing and stop to admire the view.

In the distance, beyond the marsh and swamp that dominates Bell Island,

is the Wicomico River. In all her beauty, she swims past, the sunlight reflecting

off of the water’s choppy caps. And

just at the surface, where the river meets the air, the spirit of the Wicomico

is evaporating and filling the atmosphere.

I take a deep breath, filling my lungs with that spirit, and I envision

the river in its glory: from its

beginnings as a river of seemingly endless resources, making settlement and

development possible on the very land I stand on, to its role in connecting

residents who lived here to social, political, and economic realms not only

locally, but globally, to its natural beauty that has attracted wildlife

lovers, recreationalists, and conservationists alike for over 200 years.

Through this spirit, I am reminded that this land and this Wicomico

River, bears the imprint of its human past, but it also has shaped the people

and communities based here.

Out of the corner of my eye, a long and rather old looking plank

appears. It is exposed in the low

tide as the Wicomico laps the shore.

“What’s this?” I shout, approaching the edge of the river for

closer inspection.

Bill answers, “That’s an original plank of the wharf that was built here in 1747.”

“So,

who is the architect?” I ask, figuring we should start at square one.

With a deep breath and a determined look, Bill replies, “His name is

Colonel Isaac Handy, Esquire.”

Who is Isaac Handy?

Isaac Handy

(no middle name given) was born in Somerset County, Maryland on April 13th,

1706 to Samuel and Mary Sewell Handy and was the thirteenth out of fourteen

children.

[1]

Beyond this

information, not very much of Isaac’s early childhood is known.

Scholars do know that he left his home at an early age, perhaps six or

seven, and sailed with his brother, Captain Thomas Handy, on their parent’s

sloop (ship), the Samuel and Mary.

[2]

These experiences

earned Isaac the title of Mariner before he was ten years old.

In 1721, Isaac’s father died.

[3]

Isaac was fifteen

years old. He returned to

Somerset County to find that his father had left him one half of his favorite

sloop, the other half to his brother and sailing partner.

[4]

In order to understand how Isaac would eventually treat the land, we

must first understand the values and beliefs that were instilled into him by

his father, Samuel Handy. Samuel

Handy represented the focus on economic progress that existed throughout

Somerset County in the late 17th and early 18th

centuries. Like his son Isaac,

Samuel was part of a large family and did not receive a substantial

inheritance. In order to pursue

his dreams of settling land, developing financial wealth, and building a

family, he became a redemptioner, an immigrant who lacked the funds to pay

passage to the new world and would be allowed a certain length of time to sell

their services.

[5]

Samuel

was a tobacco farmer, the main occupation of Somerset residents in the 17th

and early 18th centuries.

[6]

However, he had come

into the business at a very unfortunate time.

The tobacco market was in the middle of a thirty-year stagnation that

had begun in the 1680’s. The

only way to satisfy public demand was to develop more efficient means of

production, but these means did not come to fruition in Somerset County.

[7]

Samuel was by no means poor. Although

his business did not flourish as he had hoped, he did own vast amounts of

property at the time of his death.

[8]

This indicates that,

in addition to his wife’s inheritance, he had a prospering business at some

point in his life. In his will,

Samuel divests not only land, but also slaves, carpenter, smith’s and cooper’s

tools, and two thousand pounds of tobacco amongst his children.

[9]

The varied items in

his will not only illustrate the reliance on supplemental imports, like

carpentry and blacksmithing, which accompanied the downfall of the tobacco

business, but also the dedication to achieving economic success that was

characteristic of 18th century Somerset County.

[10]

Diversified wealth was not uncommon for a redemptioner like Samuel.

Redemptioners were not necessarily poor people, but simply children who

did not receive much inheritance. They

could easily have been sons of wealthy and educated peoples, but were not

given much with which to start out.

[11]

Redemptioners

understood that they had to forge a new path in places unknown.

This required great character and a focused drive.

Redemptioners must have been physically fit, experienced in many

different types of skills, and mentally prepared to face continual hardship.

They were pioneers, focused on establishing safe and productive living

for themselves and for their families while developing their newfound land.

The characteristics of the redemptioner can also be seen in Isaac

Handy. He was a man eager to

develop land, social status, and wealth.

Like his father, Isaac must have received much of his initial wealth

and property from his wife. Isaac

married Anne Dashiell on April 27, 1726 when he was 20 years old.

[12]

Anne was the daughter

of wealthy Thomas Dashiell of Somerset County.

[13]

Not much else is

known about Anne, which is disappointing at the least.

Isaac moved quickly and within the year purchased a 900-acre lot of

Joseph Pemberton, called Pemberton Manor, situated three miles southwest of

Salisbury overlooking the Wicomico River.

[14]

Isaac now had an

extensive piece of land, access to a river, experience with both sailing and

farming, and a growing family. It

was this land that would be Isaac’s tool to becoming a very successful man

of his time.

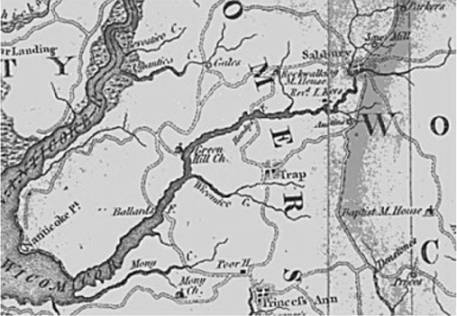

Wicomico

River, 1794. Pemberton Manor is

labeled as “Handy’s F.”

Plantation Life

Due to the widespread settlement, development, and population of the

new land, 18th century Somerset County was a time of rapid change. Beyond the tobacco market troubles, there were many other

developments occurring that had monumental effects on the settlement of the

land. For example, crafts and new

crops evolved out of the plantations as planters with larger families had more

available time on their hands.

[15]

Plantation workers

discovered that stumps could be removed during house building and land

clearing, consequently allowing for the use of the plow.

With the plow came grain crops, such as wheat, which added not only

economic benefits, but nutritional supplement.

In addition, plowing required equipment that provided work for

blacksmiths and woodworkers.

[16]

Secondly, the population was changing dramatically.

As more immigrants began to settle, the population became increasingly

“native born,” which resulted in a larger population of women and a more

even sex ratio.

[17]

Consequently, women

became the developers of the home industry.

They mastered such trades as spinning yarn, weaving cloth, butter and

cheese production, and making cider, beer, and brandy.

[18]

Furthermore, native-born populations produced larger families than

their immigrant predecessors.

[19]

This equated to more

work for the parents in order to feed and clothe a greater number of children.

As the family size grew, so did the levels of diversification on the

plantation. Parents had to depend

on the resources available to provide for their children.

Thus, they would work on extracting as much out of their plantation as

possible in as many ways possible. However,

when the children became 8 years old, they could begin to work on the

plantation.

[20]

This is also why

slaves were such an integral part of a successful plantation.

These

changes forced Isaac’s generation to view the land and use the land in new

and different ways. In this way,

Isaac Handy can be viewed as a model for his time.

His plantation serves not only as a reflection of the changes taking

place in the mid 1700’s, but also as an excellent example of the utilization

of land in the 18th century.

Isaac’s land probably did not look much like it does today. The shoreline of the Wicomico River would have been mostly

marshland, filled with species such as smartweed and wild rice, providing

nutrition for both man and animal.

[21]

The wall of trees

that I observed by the river would have had a more varied composition,

including such species as Hawthorn, Dogwood, Black Walnut, Cedar and Oak, not

to mention being altogether larger, taller, and more numerous.

[22]

A similar make-up

would have been found on Bell Island. The

forest that existed on Pemberton Manor would probably have on crept up further

on land, covering most of the property. Under

the trees, the land was extremely flat, consisting of a moist and

nutrient-rich soil. These

features of the land made profitable farming a distinct possibility.

Extensive

tree clearing would have taken place to create the room for the Handys and

their plantation. After this

clearing, the plantation became a very busy and diversified place. There was an orchard with over 200 trees of different fruit

varieties, a tannery that produced items such as shoes, a loom for making

clothes, a smoke house for hams and other meats, a kiln, and a still that

purified the fruit drinks.

[23]

The central focus of the plantation was the farm.

Isaac had developed an intricate schedule to extract the most possible

resources out of the land. Starting

in March and running until December, Isaac worked out a detailed schedule that

would include sowing flax and oats, plowing the field for Indian corn or maize

and wheat, picking cherries, harvesting the flax, wheat, and rye, cutting the

oats, planting buckwheat, planting turnips, harvesting buckwheat, and planting

cabbage.

[24]

The majority of the goods produced on the farm, as well as through the

other businesses on the plantation, would have been used to feed the growing

family. The leftovers, which were

by no means little in number, would have been used for trade.

By 1704, there were 4,437 residents in the county, which was a nice

sized market for bartering goods.

[25]

In 1725, Somerset

inhabitants had suffered such a shortage of tobacco that the Assembly

permitted payment of public debts in “country commodities,” which included

shingles, pork, beef, corn, wheat, and cider.

[26]

All of these goods

were most likely also used for bartering.

Isaac would have had a well-organized system of getting what he needed.

For example, Isaac did not have any means for producing iron.

Thus, he would have needed to acquire these goods either as import from

England, or through his neighbors. By

selling his goods, Isaac was able to account for anything that his family

needed, as well as to enhance the progress of his multiple businesses.

The

business and diversification of Isaac’s practices were a testament of his

aspirations to not only provide for himself and his family, but also to

succeed and make a difference with his life.

In Isaac’s eyes, he saw a land of opportunity waiting before him,

ready to be developed. It was

this land, the opportunities that it presented, and the changes that Isaac

exerted upon it that would dictate Isaac’s accomplishments.

Through this land and the river on which it sat, Isaac would soon

become a wealthy merchant and influential citizen.

The Rise of Isaac Handy

Summer, 1732. Life on the

plantation was good for Isaac Handy. He

and his wife spent most of their time in the good weather entertaining their

neighbors, the Winders and the Dashiells, both of which had large families.

There was major emphasis on ceremony in the Handy household, especially

with drinking tea.

[27]

The Handy’s owned a

tea table, a tea kettle, silver teaspoons, silver sugar tongs, and a silver

tea strainer.

[28]

They undoubtedly also

owned teapots and cups, and would later build a china closet to show off their

extensive collection. This

inventory is evidence that the Handy’s had enough leisure time to hold a

ceremony, had the training and manners to put it in practice, and had the

wealth necessary to purchase slaves and provide the luxury equipment.

[29]

These customs were part of a social change that was taking place in the

mid 1700’s. The same changes

that were an effect of the growing populations also applied to the lifestyles

of the Handys. Because of larger

families and more even sex ratios, parents of colonial families were able to

spend a greater amount of their time off of the plantation practicing manners

and keeping guests. Specifically

for the Handys, there were seventeen slaves, eight of which were adult hands

and two of which were old enough to work in the house.

[30]

This meant that

Isaac, Anne, and some of the older children could develop a genteel lifestyle.

[31]

This

standard of living was only possible because of the role of water,

specifically the Wicomco River, in providing a means of connection between

local families. Without the

river, the settlers would have not been able to develop the social and

economic relations that fueled the development of Somerset County.

In this sense, the river was the binding force of the 18th

century. With the isolated

populations and limited traveling capabilities, families tended to socialize

only with those who lived on or near the river.

[32]

Isaac only had a few

neighbors: John and Bridget

Winder lived at Cuttynaptico Creek, a short way down the Wicomico and James

and Ann Dasheill lived at Wetipquin Creek.

[33]

These locations were

just the right distances away so that families could still spend most of their

time together without sacrificing any business in the process. Consequently, the families had ties that continued far after

Isaac and Anne Handy. In fact,

many of Isaac’s children went on to marry members of the Dashiell and Winder

families.

[34]

Isaac’s social status began to grow through his connections with his

friends on the river, as both John Winder and James Dashiell were prominent

Somerset County citizens. In

fact, in August of 1732, Isaac was one of five people to commission a new town

in the area. As a result of the

influence of his powerful neighbors and family, Isaac easily gained this

position. Along with Isaac, John

Caldwell, (one of Somerset’s four delegates to the Provincial Assembly) John

Disharoon, (owner of the grist mill on Passerdyke Creek, now Allen) Ebeneezer

Handy, (colonel of militia and brother of Isaac Handy) and Thomas Gillis

(planter and tavern keeper at head of Quantico Creek), were commissioned by

the Provincial Assembly to divide Salisbury.

[35]

The five men were first to gather and discuss where and how a new town

would be founded. We can imagine

Isaac leading his fellow men down to the Wicomico River and engaging in a

discussion of the new settlement, while enjoying the weather and some freshly

brewed tea. Shortly following

this supposed meeting, the five men were to draft a petition that was later

presented to the Lower House of the Assembly in the July/August meeting that

suggested that there exists “a convenient place for a town at the head of

the Wicomico River.” This

petition was handled by the Somerset delegation and, following their approval,

a bill was drafted for the new town. It

was called the Provincial Assembly Act of 1732 and it authorized the

commissioners to divide fifteen acres of land into twenty lots.

They were to meet “before January 10, 1733 together on the tract of

land or some other convenient place thereto and then and there treat and agree

with the owner or owners, and the persons interested in the fifteen acres of

land for the same and after the purchase thereof.”

[36]

The commissioners wanted to build a town on the Wicomico because they

wanted to utilize its capabilities to pursue their economic ideals.

One of the most inviting features of this property was the presence of

four streams that came together and formed the river.

Those four, known today as North Branch, East Branch, Parsons Creek,

and Tony Tank Creek, and other smaller streams feeding even into them, drained

thousands of acres of land and invited the construction of dams to power

watermills.

[37]

This unique

characteristic has given support to the theory that the new town got its name

from its similarity with another town in England:

Salisbury.

[38]

After he obtained this position of power, Isaac Handy’s life changed

dramatically. He began to

develop, like many of the early settlers, “a spirit for arduous undertaking”

and a “power to sustain such an adventure.”

[39]

In essence, Isaac was

growing into the mold his father had created for him.

He had “a stout heart, as well as strong hands; able mind governed by

a will to accomplish,”

[40]

and a strong body. Shortly

after his experiences with the Provincial Assembly, Isaac developed goals and

put them into action. He began

construction on a new house to be built on his current plantation. He chose a site that would be accessible to the farm, the

orchard, and the river, and at the same time practical for easy living.

This house was to be called Pemberton Hall and would not be completely

finished until 1741.

The construction of Pemberton Hall was a marker of both the social

dominance of Isaac Handy, and his desire to develop land.

Pemberton Hall was composed of immense ten inch square beams, which

gave the house a domineering 2,500 square foot profile.

[41]

Intricately designed

and colorful Flemish Bond brickwork, the bright plaster cove corners, and the

six attractive dormer windows made up the body of the house.

[42]

There were chimneys

in each gable end, a kitchen on the east end, and a cellar entrance on the

opposite side. These lush

stylings of the house indicated the wealth of Isaac Handy, placing him in the

upper 5-6% of Somerset County.

[43]

Front-view

of Pemberton Hall. Photo courtesy

of Nicole Brown.

Pemberton Hall was not only an opportunity for Isaac to exhibit his

wealth, but also another chance to further develop his land.

For each hint of personality

in Pemberton Hall, there existed a greater sense of practicality. The square beams would have come directly from the forest

surrounding the structure and the bricks would have been made on the site’s

kiln, while the iron and glass were probably imported from England.

[44]

The cellar entrance

faced the west and allows for the easiest trip to and from the river. The house was situated northwesterly in the same direction as

the passing breeze, creating a natural air-conditioner in the summer months.

And when it got too cold for comfort, the large windows acted as a

convenient heating system.

A

few years later, after the family had settled down in the new house, Isaac

decided that he wanted to expand his capacity for business.

He purchased some land adjacent to his current plantation. The most

notable feature of this land was its vast shoreline.

Isaac must have envisioned this new purchase as being a perfect site

for a wharf, as it had direct access to the river and the Bay, a flat landing,

and was close to Pemberton Hall. Immediately,

a massive clearing operation was started and a two hundred foot bulkhead wharf

was laid down in 1747.

[45]

Isaac could have

easily seen that through the Wicomico River, he could expand his business to

different parts of the county, state, and country.

Isaac’s wharf was a perfect example of how Isaac used the land

and the river in order to benefit his economic and social aims.

Unfortunately,

we do not have any records of what business took place at the wharf.

Isaac’s export lists, maritime records, or sea trunks have never been

found. Thus, we can only

speculate what may have taken place there.

Crooked Oak Lane, which lies directly across what is now Pemberton Road

from Plantation Lane, was most likely used as the rolling road to transport

barrels of goods from the farm to the wharf.

[46]

It is also a good

possibility that Isaac invited his neighbors to utilize the wharf.

Wheat flour, bread, Indian corn, bacon, cheese, butter, staves, and

cedar shingles were probably exported up and down the east coast, as far south

as the Bahamas and as far north as Boston.

[47]

It was through his

sloops, including the George, that

he was able to send his goods in receipt for other goods or money.

This is how Isaac was able to acquire the 18 leather bottom chairs from

Boston to furnish his Great Room.

[48]

Isaac, trained as a

mariner at a young age, could have made the trips himself, therefore extending

his knowledge and experience of ship sailing and industry and making

connections in such harbors as Baltimore, Chestertown, Philadelphia, and New

York.

These connections helped Isaac develop his social status in Somerset

County. He was elected in 1747 to

fill an unexpired term of Captain John Davies in the General Assembly of the

State of Maryland.

[49]

Isaac excelled at

this position and was re-elected in 1748, ’49, ’50, and ’57.

[50]

He also became a

Justice of the Peace, a position where he dispensed justice between differing

Somerset County residents.

[51]

In this sense, we can

picture Isaac as a well-known man throughout Somerset County and across the

Bay, not only to the lawmakers, but also to the law-breakers.

The wharf and the Wicomico River, which linked Isaac to a larger world,

made all of his political success possible.

These ties with the county, as well as those he made through church,

may have helped Isaac earn the title of Colonel.

Because there is little written of his military activities, it is

thought that the Presbyterian Church granted him this title.

[52]

It was common

practice for the title to be handed out in church and county records.

Also, Isaac’s now prospering wealth meant that he could provide for a

militia.

This was the peak of Isaac’s life and business career. He was a prominent figure in mercantile, political, and

religious domains and was only in his forties.

He had a large family, a loving wife, a stable career, and a network of

friends. He had been able to

develop his land to encourage his social relations and support his business

and home life. He and his fellow

settlers became not only tolerant toward each other, but they also “worked

together; submerging their differences in the will to accomplish one end-the

developing of a community in which they would have freedom of conscience in

matters of religion while gaining a substantial economic independence.”

[53]

In this way, Isaac

set a standard for 18th century Somerset County.

He inspired his peers and future developers to not only provide for

their personal and family needs, but also to reach out into the community and

encourage the economic growth that made him successful.

Changes in the Land

Winter, 1756. Isaac Handy was now fifty years old. His plantation, orchard, tannery, and wharf were all still

running, but he had taken a smaller role in their operation.

The overseeing of the plantation would have been the responsibility of

his grown sons, George, Thomas, Isaac, and William.

Isaac

spent most of his time entertaining guests and staying in the house, attending

church, and gearing up for his last year with the Provincial Assembly. He backed away from his offices in Annapolis, as Justice of

the Peace, and as Colonel of the militia and chose to spend more time at home,

with his wife and younger children. Isaac

favored the Great Room, where he could relax by the fireplace with tea, “cherry

bounce,” a product of his still, peach brandy and other fruit drinks, while

looking out at the river.

[54]

He took a liking to

smoked hams and bacon and had mastered the cooking of the fresh seafood he

caught down by the wharf. He

knew that he had developed his land along the river to foster his social,

career, and personal relationships.

Isaac

could notice a difference in his land since his purchase thirty years ago.

The soil did not seem to be as productive as it was when he first

started growing crops on it. He had learned that he could not continue to grow tobacco,

like his father did, because it exhausted the soil so quickly.

[55]

Consequently, Isaac

was forced to use a different type of practice:

crop rotation. Isaac’s

method was to crop a certain portion of his field until it could no longer

produce any crops. Then, he would

allow this area to go fallow and develop another portion of his field.

[56]

These practices

drastically damaged the land. Isaac

witnessed his plantation evolve from one with large areas of fertile soil to

one with fewer and fewer plots of available land.

He

couldn’t have known it, but the soil on Isaac’s farmland was undergoing a

major metamorphosis. From 1726 to

1756, the soil was slowly transforming from a well-drained type that could

produce a high yield of various crops into Othello silt loam, which has poorer

draining capabilities and limited production.

[57]

In addition, the

Othello silt loam that already existed around the edges of his plantation,

near the river, was slipping away into the river and forming tidal marsh.

[58]

Thus, Isaac had to

focus on land away from the river that was fit enough to perform crop

production and rotation.

These

changes were partly due to a rising water table and the subsidence of the East

Coast.

[59]

As the water

level rose, the tidal marsh gave way to tidal swamp.

This had major implications on the health of the land and the Wicomico

River. New tree species, such as

Black Gum, Holly, Swamp Oak, Red and White Cedar started to take over the

tidal marsh. This meant that the

river could no longer receive much of the vital nutrients that the tidal marsh

would collect. It also meant that

the various species of fish that would come to the marsh as a nursery for

breeding had to find a new home. Furthermore,

the wild rice and smartweed species were pushed out and were replaced with

other species, such as phragmites, arrowhead, yellow water lily, rose mallow,

and bulrush.

[60]

In addition, the forest that once covered the entire

Pemberton Manor was rapidly dwindling away.

Isaac had planned some of this deforestation himself. He had used the girdling technique to remove trees and their

stumps so that he could quickly make a densely forested piece of land

productive.

[61]

Isaac would begin

farming near the girdled trees, and after a few weeks, he would cut the trees

completely down and use them for lumber or firewood.

[62]

Isaac required thirty

to fifty cords of wood for each of his five fireplaces (Great Hall, two other

downstairs fireplaces, one upstairs fireplace and a kitchen fireplace), which

equates to 150 to 200 cords of wood per year.

[63]

A cord of wood is

four feet by four feet by eight feet. This

is an incredible number trees to be cut down each year, and the practice

occurred throughout Isaac’s lifetime on the plantation.

In these 36 years, Isaac would have used 5400 to 7200 cords of wood.

The

lack of trees on the plantation had a great effect on the land and the river

in years to come. Because trees

were not standing to protect the land from the fierce winds, the good soil on

the farm was being blown into the river, speeding up the soil transformation

and silting in the river.

[64]

This meant that the

fish that lived in the river had a more strenuous environment to live in, and

the shad, the sturgeon, and the perch, were forced to leave the Wicomico, or

died while trying to survive.

[65]

The

river then became dangerous to humans as well.

As the water became more densely concentrated with silt, it became

harmful to drink. Isaac and

others quickly learned that a refreshing sip of the Wicomico would lead to

sickness two or three days later.

[66]

Hence, water became a

leading cause of illness and possibly death during Isaac Handy’s lifetime.

Although

Isaac may have not been a decent husband to the soil as we perceive it now, he

was not exceptionally horrible for his time.

He was a man consistent with the values and behaviors of the 18th

century. It is not fair to say

that Isaac was against protection or conservation of the land, because these

ideas did not exist in Isaac’s social forum.

However, to say that Isaac was purposely hurting the land is not fair.

He was simply doing what he believed was necessary to be happy,

productive, and healthy.

Good soil husbandry may not have existed with the English settlers, but it may have existed with the Wicomico Indians that inhabited the land on either side of Pemberton Manor, at the Rotkawawkin and Tundotank reservations. [67] The Rotkawawkin reservation was built on what is now Rockawalkin Creek, adjacent to Pemberton Manor, and was abandoned shortly after 1678. [68] Isaac Handy must have realized that his land was located alongside what was formerly an Indian reservation. By seeing the remnants of the former settlement, Isaac would have decided that the land suitable for the Indians was prime land on which to live. The Tundotank reservation was located diagonally across the river from Isaac Handy’s land, along Tonytank creek, and would have subsisted at the same time as the Handy plantation. These reservations reflected the state of the land before Isaac’s settlement, which was much different than the state of the land in the mid-18th century.

The Indians settled the land with minimal impact. They lived close to the Wicomico, because the land was suitable for farming, was accessible to the river, and was close to the food source, the tidal marsh, which provided not only plant life but also animal life on which to feed. The towns they formed on the waterfront consisted of many small homes made from local materials. This where the name “Wicomico” comes from, which means “Place where houses are built.” They were widely dispersed and used trees for protection, which prevented massive clearing. They were also not permanent communities. The Indians would move between towns and campsites to accompany the changes in their diets. [69] In this sense, the Indians were able to live safely without drastically altering their environment.

Fishing, hunting, and farming comprised the bulk of the Indian’s impact on the land. However, the Indians were able to use all of the resources of the land equally without depletion. In the spring, Indians relied heavily on the land and water animals for nutrition, as their plants were not yet ready to harvest. From April to June, the Indians would rely on the nuts and acorns gathered from foraging in the late fall, as well as the plants, such as Tuckahoe, and berries that naturally grew around them. In the summer and fall, the Indians feasted on the beans, squash, and corn grown on the farm. The farming practices used by the Indians were designed to be efficient, yet undisruptive. They used small-scale clearing, digging stick agriculture (no removal of stumps), intercropping, and no fertilizers. [70] By shaping their diets around what their surroundings had provided for them, the Indians were able to protect nature and enjoy its goods.

The effects of Isaac Handy’s development on the land, when compared to that of the Wicomico Indians, were a powerful indication that the land was changing. A land that once allowed for sustainable development and growth now saw its resources almost completely depleted in less than fifty years. These changes would impose greater limitations on succeeding landowners and would determine the course of progress along the Wicomico River for future generations. [71]

Death

Isaac Handy died on November 12th, 1762 at 2 a.m. from unknown causes.

He wished to be buried at his home and love:

Pemberton Manor. He was

probably dressed in his favorite clothing: buckled shoes, silk stockings, a

flowered waistcoat draping almost to his knees, and a cauliflower wig topped

by a three-corner hat.

[72]

In his right hand

would have been the sword that he was always known to be carrying, a short,

three edged instrument, with a broad, heavy silver handle.

[73]

His grave is unmarked

and in an unknown location.

Life after Isaac Handy

After

Isaac Handy passed away, Pemberton Manor became a very different place. The apple, peach, and cherry orchards all gradually

disappeared, as residents found it easier to purchase beverages and fruits

from neighbors, instead of spending countless hours and energy maintaining the

trees. The same was true for the

old loom and still, which subsequent owners had no use for, and thus they

ceased to exist. Eventually, the

wharf also stopped being managed, as the growing city of Salisbury out

competed Pemberton Manor.

By

the 1900’s, the only remnants from Isaac’s time were the open farming

field and the house, Pemberton Hall. The

field became home to new types of crops, including watermelons, which did not

demand fertile soil. The land

could not produce the same way as it used to.

The subsequent owners progressively phased out the field as a primary

business and concentrated on alternate endeavors in the city.

At

some point, an owner decided to build a new farmhouse closer to the road,

because automobiles started to provide for better transportation.

Hence, Pemberton Hall became a tenant house. Because it was not used continuously, it grew more and more

into disregard and neglect. Pemberton

Hall had, in essence, became an abandoned house rather than a plantation site.

We

don’t know why the neglect occurred, but it is certain that the property

owners did not value the land enough to preserve its history and culture. The subsequent owners of the house obviously did not use the

plantation and house for the same reasons as Isaac Handy.

This is understandable, as the times had definitely changed since 1726.

But, what had changed to create such a difference in values?

Isaac made sure that his home and land were at all times productive and

busy, always looking ahead to bigger and better business.

After his time, the zeal for independence and discovery on the Eastern

Shore began to switch focuses. Citizens

remained eager to succeed economically, but were not so interested in

developing their own ways of production.

They began to rely more heavily on the growing city of Salisbury as a

source of supplementation. The

means of production for the city focused more on a few farmers, as well as

importation from outside sources.

These

changes were amplified as the resources of Pemberton Manor became more

difficult to extract. The land

had become something completely different from Isaac’s time and thus, old

farming techniques would not apply to the new soil.

Wind borne erosion and the rising water table had transformed the area

into a rough, low draining soil with little yield.

[74]

Consequently, owners

of Pemberton Hall had to look elsewhere for land suitable for farming.

At the same time that Somerset County was undergoing this

transformation, there was a different type of change occurring among the

richer people of the United States. People

like John Rockefeller were spreading the idea of preservation of colonial

history, which spawned the first major undertaking:

Colonial Williamsburg. Eventually,

conservation of a historical place became accepted in the social and political

realms, and new projects began popping up along the East Coast. The Historical Preservation Movement, as it is known, would

soon make its way to Pemberton Hall, and change the future of the land on the

Wicomico River forever.

The Restoration Proclamation

“Pemberton

Hall and this property had been acquired by several developers:

the Raynors, Faw, Boyce, and Twilleys,” Bill said, still going strong

in the middle of our two hour tour, “some very forward people, Polly Burnett

being one of them, said, ‘Hold it folks, we can’t have that come down.”

[75]

In

1963, Pemberton Hall was almost bulldozed to the ground in favor of making the

land into a new subdivision.

[76]

And it probably would

have happened, if it weren’t for a Mrs. Polly White Burnett.

Polly Burnett formed the Pemberton Hall Foundation, after failing to

convince the Maryland Historical Society to save the house from destruction.

After gathering a small army, Mrs. Burnett and the rest of the

Foundation went to the county to see what could be done to save the house.

The county gave them six months to stabilize the house, or it would

come down.

“If

you look at it from a business perspective,” Bill explains, trying to

comprehend why the County would not want to save probably its most

historically important piece of land and Pemberton Hall, “it’s hard to do.

You just bought a piece of property and sitting in the middle is

something you don’t want, and that is in the way of being able to farm it

and develop it. If you weren’t

interested in history, you don’t look at it and say, ‘Wouldn’t it be

beautiful?’ you say, ‘I have to get rid of it.’

I’ve seen it happen time and time again.”

Fortunately,

Mrs. Burnett was able to raise the money to stabilize the house.

The Foundation took all donations, from a few pennies to large checks.

They received grants from the Maryland Historical Trust.

They held an antiques auction at the Wicomico Civic Center.

They researched the most financially reasonable ways of stabilizing the

house, such as convict labor, and made the most of their money.

Soon,

the house was officially stabilized and was well on its way to being fully

restored. Now, questions arose

about how to restore Pemberton Hall. As Bill explains:

“The

standard of the time was as Williamsburg did.

You went ahead with what looked ‘good’:

Oriental rugs, high style furniture, etc.

Now, that is a hindsight way of looking at things.

It was a social thing as well as a preservation thing.

Polly’s approach was different than it is now.”

“What

do you think changed?” I asked

“It

changed with more research. Since 1976, there has been a tremendous amount of information

that has come out about 18th century life. So, when that information started becoming available, some of

us wanted to tell the whole story.” Bill

smiled.

And

the truth is the story now told at Pemberton Hall.

The truth can be found in the corner of Great Hall, where there is a

boot and a sock that reflect Isaac’s old boot and sock.

And the truth can be found in the unfinished well, which, because of

its wooden lining, had to be left unfinished for safety reasons.

And the truth can be found in the two mirrors, ten chairs, and two

tables that represent the two mirrors, eighteen chairs, and three tables that

were in Isaac’s possession.

“As

a historian, you tell the whole truth and you let the chips fall as they may:

right, wrong, liked, disliked, you tell the truth.

And you don’t slant it to one bias or another,” Bill said.

However,

even when we tell the truth through the restoration of Pemberton Hall and the

plantation, we are choosing to neglect other truths that still exist, such as

the presence of Native American reservations along the Wicomico River.

In this way, Pemberton Historical Park represents only a portion of

Somerset County and Salisbury’s past, though it is significant to history

and Eastern Shore culture.

The

Foundation has worked steadily since 1963 to design restoration projects for

Pemberton Hall. Because of a lack

of funds and a desire to be completely accurate, the projects have taken more

time than originally predicted. This

has caused some agitation in the community.

However, this slow, but sure process has prevented many errors that

could have happened while restoring the structure.

Not

all of the citizens of Wicomico County backed the restoration of Pemberton

Hall. Some felt that the costs in

repairing the run-down house were not money well spent.

In a series of “Letters to the Editor,” printed in The Daily Times

in 1972, Mrs. Robert Larmore of Princess Anne, MD and Mrs. Burnett exchanged

opinions on the restoration of Pemberton Hall.

In her reply to an article highlighting the restoration projects, Mrs.

Larmore remarks, “Can our state afford to contribute $15,000 when our sick

and aged can’t have a comfortable and pleasant place to live, with adequate

care?” She continues, “I just wish more people of Mrs. Burnett’s

zeal and persuasive powers would become interested in how things are now, and

put as much effort into some changes for betterment of now and the future, as

they do to reflect the past.”

[77]

This

article, published on Sunday, was met with a reply from Mrs. Burnett herself,

just two days later. She responded, “[Mrs. Larmore’s accusation] is palpably

untrue that for the sake of the public image of the restoration I feel it

cannot go unchallenged.”

[78]

She goes on to

report on the details of the research, costs, and details of the exact

furnishings of the house.

Mrs.

Larmore’s comments cannot be generalized to the entire population of

Wicomico County, but we must agree that a good part of the public did not want

to see this restoration take place. Why

not? Most residents, like Mrs.

Larmore, were outraged at the costs of the projects and felt that they could

be better focused for what they thought were more important reasons.

Although it is not my position to debate whether the “sick and aged”

or historical preservation is more worthy of money and value, the fact that

some members of the public did not want to restore a local and historically

significant piece of property says something about what the people of the time

did and did not value. Historical

culture just did not rank highly in Wicomico County’s hierarchy of values.

At

the same time that the Foundation was working to preserve the land, other

parts of the county were being rapidly developed.

In 1987, there was a column in the Daily Times newspaper that had a

notice of a hearing for zoning to annex the property surrounding the park.

A developer from New Jersey had watched the restoration of Pemberton

Hall and slowly bought up all of the developing rights on three sides of the

park. The developer went to the

city council and organized a hearing to annex the property into the city.

“We

had one week, so we put out feelers to all of the preservation minded people

in the county and put 200 people in that hearing room.

The city had two hearings. They

turned down the first reading. They

said to us in the courtroom, ‘We are going to turn this down now.

If it comes up again we are going to give it to [the developer] unless

you can buy it, because we are not going to take the profit out of it for

these people,’” Bill said.

The

heat was now on, and action had to be taken to save the land.

Bill, Russel Dashiell, and a few others stalled the developer while

Gary Mackes went to the Governor’s office and the Department of Natural

Resources and got a promise of $400,000 to buy the property.

The county agreed to give $200,000 and in the meantime, the developer’s

option ran out on the land. Bill

and his cohorts were able to purchase it for $600,000 and thus, saved the park

from being surrounded on three sides by subdivisions.

[79]

However,

they were not able to save all of the land previously owned by Isaac Handy.

Half of the land that made up Isaac’s original plantation had been

bought by developers and transformed into a subdivision called Harbor Pointe.

Harbor Pointe now rests on the other side of nearly 5 miles of trail

that are included in the Pemberton Historical Park area.

Present day Wicomico County: Pemberton Historical Park (white) is situated directly next to Harbor Pointe Development (yellow).

“When

they were developing Harbor Pointe, you have to say enough is enough and I can’t

do anything about it. And it hurts. For

example, I know where a number of prehistoric Indian sites are.

I can’t do anything about it. That

is also the site of Handy Hall. (Handy Hall was built by George Handy, Isaac’s

son, in 1750). They started

excavating for this house and lo and behold they hit the foundation of Handy

Hall. That is one of the most important structures in the county

and there is nothing you can do about it.”

And

herein lies the juxtaposition of values that characterize Wicomico County.

In Pemberton Historical Park, we see the strong senses of preservation

and history coming to life. But,

surrounding that area, we see the same economically driven ideals that have

been carried over from Isaac Handy’s time.

To me, it didn’t make much sense.

“Why

would there be so much preservation in one area, but right next to it, heavy

development?” I asked.

“We

had to concentrate it. It had to be done and you have to make some hard choices.

You can’t save everything. If

you try to save everything, you get nothing,” Bill explained carefully.

He was obviously speaking from deeply personal experiences.

The

development of Harbor Pointe on the banks of the Wicomico marks a transition

in the value of waterfront property. Rather

than a scenic amenity, waterfront property in the 18th century was

necessary to maintain good business, as rivers acted as the major highways. With industrialization, rivers soon grew to become noisy,

busy, and an overall disagreeable place to live.

This, in addition to the development of roads, the choice property

became that closer to roads. More

wealthy homeowners began to construct homes nearer to roads and further from

waterways, to avoid distractions and enjoy the natural settings around them.

Waterfront property was left to poorer families, who could not afford

to move from the unattractive river. As

business gradually moved from the river and to the highway, suburban sprawl

attracted families to move into suburbs and away from the river.

As less people lived on the river, the property once again became the

choice for the richer people of the county.

Specifically, along the Wicomico, the industrialized portion of the

river is associated with apartment complexes and town homes, whereas the less

developed portion of river is filled with larger homes, mansions, and

exquisite subdivisions, like Harbor Pointe.

When

dissecting the values of the developers and preservationists, we must take the

same mindset as we did with Isaac Handy:

we must regard them as people of their time.

Unfortunately, in 1960’s Salisbury, many people valued land by the

dollar. Shockingly, this fact remains basically unchanged since Isaac’s

time. Along the same lines, the

land that was valued economically changed differently from that which was

valued for restoration and conservation.

Unless land had some historical significance that could be proven by

willing individuals, developers had no problem developing their land. Ironically, in order to preserve Pemberton Historical Park as

a monument to our past, we had to fight against the very same economic values

that Isaac Handy and his peers held 300 years ago. This is not criticism of developers. Developers probably believed that developing the land would

make the county a better and safer place in which to live. However, until the value of land is viewed from a less

economical and more culturally significant standpoint, all land is vulnerable

to development, even that which may contain some of the richest history that

exists in the United States. This

is why the juxtaposition of values remains today.

Just

as Isaac Handy’s economic value of the land enacted changes on that land, so

did the restoration and conservation of Pemberton Manor.

Presently, Pemberton Historical Park is the second largest open park

out of the 64 open parks in Wicomico County.

The land looks much different from the mid 18th century:

there are no bustling industries, no slaves, more forests, no boats

unloading on the wharf, and fewer buildings.

As the development of the land has slowed, the life underneath and

above the surface has begun to return. The

soil is beginning to restore itself with nutrition, as evidenced by the growth

of ruderal species, such as annual weeds, that have replaced the stretches of

sand that once dominated the property. Similarly,

along the banks of the Wicomico and on either side of the open field, tree

species like the White and Red Cedar have returned to form growing forests,

wetlands, and swamps. And perhaps

the most celebrated homecoming is that of the people. There has been a steady increase in the number of visitors to

this land since the restoration of Pemberton Hall and Manor.

There always seem to be a few cars parked in the oyster shell parking

lot and a few trail hikers making their way around paths enjoying the prime

natural setting on the Wicomico River. In

so much as the land continues to be conserved and valued, it will continue to

replenish itself. Noticing these

changes brings up an interesting question:

What would this land have looked like if it were never saved?

Beyond

Pemberton Hall, there are just two other structures on site:

an educational center and an historical museum.

This may strike some as strange. They

see a historical park supposedly preserving 18th century life and

wonder, “Would Isaac Handy have built an educational center on his land?” When we ask this question, we must realize how much has

changed since Isaac’s time. Today,

at Pemberton Historical Park, people believe that the land can be conserved

not only as a record of life, but also as a means for developing environmental

awareness. Pemberton Historical

Park celebrates the value of land, in its historic, cultural, educational, and

natural senses. In doing so, the

park not only commemorates our colonial past, but the present day in which we

live.

The

bottom line is that value differences affect the land.

From the rise of Isaac Handy, to life after Isaac, to the restoration

proclamation, the values that people held onto were reflected in the way the

land was treated. And, consequently, the treatment of the land brought upon new

situations and opportunities for the next generation.

Without Isaac Handy’s development of the land, we would have had no

reason to preserve it. However,

if the land were not properly treated to begin with, Isaac would have had no

reason to develop it. This simple

recognition that the use of the land has changed is also evidence that the

values of the people have changed.

When

we inspect our values and why we believe in them, we must realize what impacts

they may have on the land. We must recognize how we value land. Is it economically valued or culturally valued? Is there a

healthy balance? These are

questions that we must answer for ourselves in order to protect both the land

and the needs and values of our society.

Once we, including both citizens and lawmakers, begin to treat the land

in accordance with balanced values, it cannot be mistreated by harmful

development or negligence.

Bill

Wilson sits across from me, addressing his future relationship with the park:

“As long as I am here, that house will never have barriers in it. I want it to be a living history version.

I want to be able to take school kids in there, and sit them on the

floor, and dress them up and talk to them and pick things up to show them and

talk to them about history and have it come alive for them.

And that is fun. And if it

stops being fun, I guess I won’t be involved.

What else can I answer?”

“I

think that is it. I’ve gotten a

wealth of information,” I say, standing up to shake Bill’s hand.

Bill

walks with me downstairs, out of the education center and to my car, still

chatting about his ideas for new education opportunities at the Park.

I say goodbye, and am on my way down Plantation Lane. As I am making my way around the dogleg near the wharf, a

vision forms in my head. Where

Pemberton Hall was once standing exists a modern looking house with a deck and

a trampoline and a Gazebo by the river. Next

to it, and all around it, are exact replicates.

There are roads, street lamps, and stop signs. It is a pleasant little neighborhood called “Pemberton’s

Good Will.” Suddenly, my mind

flashes back to reality, and I am on the gravel road passing the worm fences

and baby apple trees. A warm

feeling has just blossomed in my spirit, one of thankfulness for the

preservation minded people who had the desire to save and restore this land. I look back to see Pemberton Hall, the open field, the

fences, and the Wicomico River in the distance.

I am happy that within my vision exists not only a monument to the rich

history of the Eastern Shore, but also a true reflection of how we value and

treat land today in Salisbury, Maryland.

[1] Handy, Isaac W, D.D. “Annals and Memorials of the Handys and their Kindred.” William L Clements Library. Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1992 p.17-19.

[2] Handy, Isaac W, D.D. p.17-19

[3] Handy, Isaac W, D.D. p.17-19

[4] Samuel Handy, Sr.’s Will. Prerogative Court of Maryland. Liber: 17 folio 24

[5] Handy, Isaac W, D.D p.2-4

[6] Samuel Handy, Sr.’s Will. Prerogative Court of Maryland. Liber: 17 folio 24

[7] Green Carr, Lois. P.353-354

[8] Samuel Handy, Sr.’s Will. Prerogative Court of Maryland. Liber: 17 folio 24

[9] Samuel Handy, Sr.’s Will. Prerogative Court of Maryland. Liber: 17 folio 24

[10] Green Carr, Lois. P.353-354

[11] Per Bill Wilson

[12] Handy, Isaac W, D.D. p.17-19

[13] Handy, Isaac W, D.D. p.17-19

[14] Truitt, Charles J. p.20

[15] “Staple crops and Urban Development in 18th Century South.” Perspectives in American History, x (1976) 5-78

[16] “Staple crops and Urban Development in 18th Century South.” Perspectives in American History, x (1976) 5-78

[17] Russel R. Menard, “Immigrants and their Increase: the process of population growth in Early Colonial Maryland” in Aubrey C Land, Lois Green Carr, and Edward C Popertive, etc. “Law, Society, and Politics in Early Maryland” (Baltimore, 1977) 98-99

[18] Green Carr, Lois. P.354

[19] Menard, Russel R. p 98-99

[20] Menard, Russel R. p.98-99

[21] Pemberton Historical Park Sign

[22] Per Bill Wilson

[23] Isaac Handy’s Inventory. Inventories of the Prerogative Court. Liber 81 folio 303 and Bill Wilson

[24] Bradley, Sylvia. “Pemberton News” April, 1982. Vol 3. No. 2

[25] Stump, Bruce Neal. “Somerset County, A Pictoral History.” 1985. Donning Co. Publishers, Norfolk. p.20

[26] Truitt, Charles J. p.20

[27] Green Carr, Lois p.378-379

[28] Isaac Handy’s Inventory. Inventories of the Prerogative Court. Liber 81 folio 303

[29] Green Carr, Lois p.378-379

[30] Isaac Handy’s Inventory. Inventories of the Prerogative Court. Liber 81 folio 303

[31] Green Carr, Lois p.381-382

[32] Truitt, Charles J. p.20

[33] Truitt, Charles J. p.20

[34] Handy, Isaac W, D.D. p.17-19

[35] Archives of Maryland, vol xxxvii. Proceediings and Acts of the General Assembly of Maryland. May, 1730 to August, 1732, p.537-540.

[36] Archives of Maryland, vol xxxvii. Proceediings and Acts of the General Assembly of Maryland. May, 1730 to August, 1732, p.537-540.

[37] Bradley, Sylvia and Thompson, G. Ray. “Historic Salisbury: An Exhibit and Catalogue of Documents and Artifacts Tracing the Growth and Evolution of the Town of Salisbury in Maryland. c.1730-1960.” April, 1991. Salisbury State University. P.3

[38] Cooper, Richard. “Salisbury in Times Gone By” p.20

[39] Torrence, Clayton. “Old Somerset on the Eastern Shore.” Whittet and Shepperson. Richmond, Virginia, 1935. P.275-77

[40] Torrence, Clayton. P.275-277

[41] Truitt, Charles J. “Historic Salisbury Updated: 1662-1982” Country Life Press. New York, 1932 p.24

[42] Truitt, Charles J. p.24

[43] Per Bill Wilson

[44] Truitt, Charles J. p.24

[45] Pemberton Hall Foundation publication, 2002.

[46] Per Bill Wiilson

[47] Bradley, Sylvia. “Pemberton News” Jan, 1982. vol 3, no.1

[48] Per Bill Wilson

[49] Handy, Isaac W, D.D. p.17-19

[50] Handy, Isaac W, D.D. p.17-19

[51] Handy, Isaac W, D.D. p.17-19

[52] Handy, Isaac W, D.D. p.17-19

[53] Torrence, Clayton. P.275-277

[54] Schaun, George and Virginia. “Everyday Life in Colonial Maryland” Greenberry Publications. Annapolis, Maryland, 1959. p.4

[55] Per Bill Wilson

[56] Per Bill Wilson

[57] Green Carr, Lois p.344-345

[58] Green Carr, Lois p.344-345

[59] Green Carr, Lois p.344-345

[60] Stribling, J.M, Barse, A.M., Grecay, P.A., Hunter, R.B., Maloof, J.E., H.E. Womack. “Ecology 225 Lab Manual, Spring 2002” p.36

[61] Per Bill Wilson

[62] Per Bill Wilson

[63] Per Bill Wilson

[64] Per Bill Wilson

[65] Per Bill Wilson

[66] Per Bill Wilson

[67] Rountree, Helen, Davidson, Thomas. “Eastern Shore Indians of Virginia and Maryland.” University Press of Virginia. Charlottesville, Virginia. 1997. p108-110.

[68] Rountree, Helen, Davidson, Thomas. p.113

[69] Rountree, Helen, Davidson, Thomas. p.33-34

[70] Rountree, Helen, Davidson, Thomas. p.34-35

[71] The comparison of English Colonist and Indian effects on the land is similar to that described by William Cronon in his book, “Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England.” Hill and Wang. New York, 1983.

[72] Schaun, George and Virginia p.4

[73] Handy, Isaac W, D.D. p.17-19

[74] Per Bill Wilson

[75] Per Bill Wilson

[76] Per Bill Wilson

[77] The Daily Times, Jan. 23, 1972

[78] The Daily Times, Jan. 25, 1972