Chapter Seven:

Delmarva And Its Poultry Industry

Amanda Sprows

In

1923 a hardworking housewife, by the name of Cecile Steele from Ocean View,

Delaware with fiery red hair and a personality to match, mistakenly attained a

brood of 500 chickens a vast increase from the usual fifty that were used in egg

production. Cecile, being a smart

and industrious person, decided to keep the chicks rather than send them back

and used this mistake to her advantage. She

saw the chance to make a little extra cash and she took it.

When 38% of them reached two pounds live weight she sold them for 62

cents a pound. Cecile, with her

savvy business sense, did not stop there. The

following year she increased her profits by selling 1,000 chickens for 50 cents

a pound.[i]

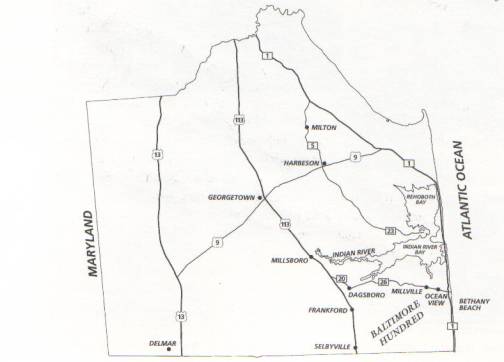

As

word of Cecile’s profits spread, meat type chickens, as they were described,

began appearing in Sussex and Southern Kent counties in Delaware, Worcester,

Wicomico, Somerset, and Caroline Counties in Maryland, and finally Accomack

county in Virginia. Before this

time chicken were raised in small amounts as barnyard fowl.

They were considered useful only for egg producing purposes.

Egg hatcheries were the first chicken related industry.

At the end of World War One a number of poultry firms were producing

table eggs to be sold for market. After

Cecile’s discovery this all changed. With

news of her profits, the number of broilers produced on the peninsula jumped

from 50,000 in 1925 to seven million in 1934, and by 1941 forty-eight million

broilers were produced. The

Delmarva Peninsula was on its way to pioneering an industry whose strength would

grow to proportions no one quite anticipated.[ii]

Mistakes happen in life, and it is often from our mistakes that we learn or gain the most . It is hard to believe that the mistake of one woman in 1923 lead to the birth of a multi-billion dollar a year industry that got its start on the Delmarva Peninsula and continues to exist there today. It has been almost 81 years since the poultry industry first appeared and the it has had a great impact on the Delmarva region. The Delmarva Peninsula, because of attributes like its geography, work forces, and climate, was able to give rise to what has become an incredibly profitable industry for the region. However factors such as the labor force that contributed to the early success of this industry, are experiencing difficulty today. The once abundant labor supply for the chicken industry has undergone a transformation and now consists almost solely of an immigrant labor force which has been carried over from the fall of the trucking and canning industries and the diminished need for migratory workers. This immigrant population while extremely valuable in providing necessary labor to the Peninsula’s poultry industry, is causing a shift in the culture and demographic of the region. In addition the region is facing special pressures of land development. Loss of farmland is accelerating and farmers are facing pressure as land in the area is being developed and urbanization is on the rise. Farmers are becoming torn between making a large profit by selling their farm or keeping their farms because of the importance it has for our area. Thus the poultry industry did not just transform the agriculture of Wicomico county and the rest of the peninsula, but the culture, demographic, and the cityscape.

Many

factors contributed to the early success of the poultry industry on the Delmarva

Peninsula. The mild climate of the region keeps heating and fueling costs at a

minimum, while the sandy soil facilitates drainage of liquids in chicken manure,

thus helping to control disease. Building

costs were also able to be kept at a minimum because much of the peninsula was

covered by lush green pine forests in the 1920’s and 1930’s making timber

easily accessible and inexpensive. Additionally,

the peninsula is also in close proximity to important markets in America, such

as Philadelphia and New York, so finding a market for the chickens was not a

problem. Finally, many of the

workers had prior experience with chickens by raising them as barnyard fowl and

using them for the production of table eggs.[iii]

Not

only were building costs low, but land was cheap as well, and banks, seeing

dollar signs, were eager and willing to give growers credit.

In the state of Delaware there was a tendency among farmers to rent their

land rather than own it during the time that the poultry industry was expanding.

One of the things that was appealing about the chicken industry for the

initial farmers was that a large amount of land was not needed.

This meant that one could become a chicken farmer on a small amount of

land and thus one did not have to be wealthy to become a chicken farmer.[iv]

The

twenties were a hard time economically for the Delmarva Peninsula, many of the

farmers here could not compete with the farmers of the west.

They had a hard time competing with staple crops such as corn and wheat.

Trucking crops to Baltimore and further north was one of the only

competitive advantages the farmers of the region had going for them.

Many of these farmers had to rely on two jobs, farming and fishing.

It is in this context that geography helped play a role in expanding the

chicken industry on the Delmarva Peninsula.[v]

Geography

made available a labor force as a result of the opening of the Assawoman Canal.

In the 1920’s the salinity levels in the waters of the Indian River Bay

Barrier Islands were changing. These

barrier islands helped to protect the eastern coast of the peninsula from the

harsh and damaging surf of the Atlantic Ocean as well as the bays of the region.

However, every time that the ocean backed up bay waters broke through the

barrier islands and forced open a new inlet or silted up an old inlet causing

salinity levels in the bay to rise or fall. These events had a significant impact on the local marine

life. In 1925 the closing of the

inlet from the Atlantic Ocean caused hundreds of watermen to lose their jobs.[vi]

The closing of the inlet caused decreases in the catch of local fisherman who

depended on oysters, crabs, and other various marine life, which was devastating

to their income.[vii]

It was at this time that news of Cecile Steel’s discovery was spreading

throughout the region. Many of

these men in desperate need of money and having no other alternatives, were then

able to move into jobs in broiler production as it slowly expanded throughout

the region.

Williams, William H. Delmarva’s Chicken Industry: 75 Years of Progress. Delaware: Delmarva Poultry Industry Inc, 1998 pg. 10.

The cost of labor was low in the early days of poultry processing which

was important because many of the early techniques in processing were extremely

labor intensive. A hatchery

provided chicks for broiler production. Many

hatcheries started off producing chicks for egg production but as broiler

production increased, the

hatcheries switched to producing chicks for the broiler growers. When chickens were first delivered from the hatchery,

“chick guards” made of cloth covered wire were used to keep the young

broilers warm by concentrating them next to the broiler stoves.[viii]

Initially, these young chickens had to be fed manually.

This meant that the growers had to place paper around the brooder stoves

and put the food on the paper. They

then filled numerous water crocks and placed them around each stove.

When the chickens were big enough to eat out of a feeder the chicken

house was opened and growers used different techniques to feed and water the

adult chickens. At this stage each

grower emptied one hundred pound bags of feed into a wheelbarrow or carrier and

walked around the house filling five foot long troughs with the feed. Water was stored in a pressurized barrel that allowed it to

drip into watering trays and the drip turned on or off according to the water

level.[ix]

This managing of the stoves and hauling of the feed was an exhausting and

unpleasant step in raising broilers. This

method was hard labor and often time consuming, as one early chicken farmer

recalls:

“When I got involved in the poultry

industry, chickens were hand fed. You can't imagine how excited we were when

they invented automatic feeders. Having

gone to these, we saved a great

deal of time. This in turn allowed us to care for more chickens, therefore, we

built new chicken houses.” [x]

The initial growers did not keep the chickens in the chicken houses all

the time, they were allowed to roam

free in the yard during the day and were brought back into the chicken house at

night. In the yard chickens would

feed on worms and other insects and eventually when back in the chicken house

they would be feed the corn. There

were commercial chicken feed companies around at this time as well that provided

feed for the chickens. Thus early

on as the industry was expanding on the peninsula there was a combination of

feed being bought and feed being grown. Eventually

when the chickens were kept strictly inside the house by the 1940’s, the

chicken feed industry was more commercialized and all feed was commercial feed.[xi]

Broilers

being raised during World War II, still being let free to roam chicken yard

Williams, William H. Delmarva’s Chicken

Industry: 75 Years of Progress. Delaware: Delmarva Poultry Industry, Inc,

1998 Pg. 26.

In

the early days growers had to live in close proximity to their houses in order

to keep a close eye on their chickens. It

was almost as if the growers lived, breathed, and ate chickens, twenty-four

hours a day because so much went into the care of the chickens.

Some growers owned more than one farm hiring both male and female

caretakers to live on additional sites.[xii]

In fact, during the 1930’s and 1940’s many chickens were kept in

houses similar to the chicken houses of today, except that they had a two-story

structure in the middle. On the ground level of the structure was a room which stored

feed and other materials needed for the chickens, while the second story was an

apartment for the chicken farmer and his family.[xiii]

Once the chickens were big enough to be sold, growers accepted the best offers and made arrangements with the buyer for the weighing and pick up of the chickens. The initial markets for the chicken were Philadelphia and New York and the chickens were shipped live to these markets. In order to be transported the chickens had to be loaded onto trucks under the cloak of nightfall by what were known as chicken catchers. Evening was the preferred time to load the chickens by these chicken catchers because the chickens were groggy and easily able to be caught. Once the chickens were sold the entire chicken house had to be cleaned of droppings and sawdust, to ensure the health of the next batch. This process of shipping chickens live continued up until the 1950s when processing plants grew more popular.[xiv] Therefore, pre-World War II chickens were raised primarily by local farmers, many of whom were formerly fishermen, were hand fed, and shipped live to urban markets.

The

emergence of processing plants began in 1938 with founders Senator John Townsend

and his son Preston. At this time

this father and son team set up a hatchery near Swan Creek Orchard in Millsboro,

Delaware. They built chicken houses

on land that they had recently acquired and filled the houses with chickens from

their hatcheries, hiring people to take care of these chickens.

Townsend then eventually set up a processing plant in that same year, as

the demand for chickens increased during World War II.[xv]

By

1942 ten peninsula processing plants had the ability to slaughter, dress, and

ice pack a combined total of thirty-eight million broilers a year.

The processing plants allowed the chickens to be killed and dressed

before they were shipped to the markets. Processing

plants were a great improvement in the industry because growers no longer had to

worry about loss of profit from chickens losing weight in the transfer to

market. Chickens could now be

killed prior to shipping at their prime weights.

However, the work in these first processing plants was very demanding;

the technology was primitive, and it took a significant amount of manpower to

produce the chickens.[xvi]

Killing

the chickens involved slitting the throats, bleeding, and scalding the broilers

to loosen the feathers so they could be picked.

The chickens then were hung by plant workers on an overhead conveyer

belt, and picked with mechanical pickers. Wax

was used to aide in removing the finer feathers on the body of the broiler to

ensure a smooth, well cleaned chicken. Finally

the remaining food was removed from the bird by plant workers with the head and

feet remaining attached. This was

the process used in most processing plants in the 1940’s while the industry

was expanding.[xvii]

While poultry production continued to grow on Delmarva, chickens still remained a more expensive and less popular meat than cattle or pork. This was mainly because chicken was not as efficiently produced as it is today. Diseases were rampant and disease control was not up to the standards that it is today. Also it was not until the 1940’s that plump chickens were being produced, before this time breeding processes were more primitive and chickens did not have the weight they do today. After the 1940’s chicken were produced more efficiently. Farmers began to learn how to grow more chickens in a faster period of time as a result of technological advances such as mechanical feeders, and developing better modes of disease control.[xviii] In 1940 the average American ate 124 pounds of beef, pork, and mutton annually, while only 14.1 pounds of chicken were consumed annually.[xix] The demand for chickens placed on the industry during World War II would change this.

World

War II and the Poultry Industry

Wicomico

County sent 2,738 men into the service during World War II out of a population

of 34,530. On the homefront, the

community had to re-adjust itself to the changes occurring as a result of the

war. All resources in the

community, including manpower, were being put into the war effort.[xx]

In Wicomico County and throughout the Delmarva Peninsula much of this war

effort was going into the production of chickens to fill the bellies of the

troops overseas.

Expansion

of the industry by the war was mainly the result of two factors.

Chickens could be moved from birth to the slaughter house at a faster

rate than cattle or pigs. Second, the peninsula has easy access to many

seaports.[xxi]

As a result of these factors, broiler chickens became an important part

of the diets of both the armed forces and civilians.

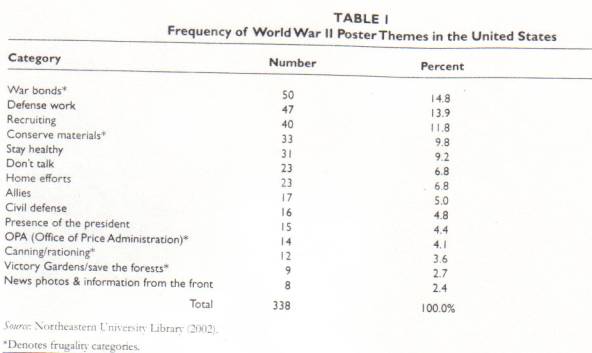

The government at this time rationed red meat because it took more grain

to feed cows than it did to feed poultry. Red meat was not the only thing the

government rationed during the war. Many

common goods such as gasoline, coffee, butter, shoes, and sugar were rationed as

well. The government was trying to ration that which was in short

supply which led to changes in product and packing materials.

A major effort was being put forth into the production of posters to help

encourage wartime frugality.[xxii]

The national government contracted processing plants and employed

advertising to convince poultry growers to supply plants with the chickens.

This was in an effort to help meet the demands.

By 1945 Delmarva poultry processing plants supplied the army with

approximately 1.5 million pounds of poultry weekly.[xxiii]

U.S. broiler production in 1945 was 366 million with an average live

weight of 3.03 pounds.[xxiv]

Delmarva therefore in 1945 accounted for 7% of the nation’s broiler

production.

Witkowski, Terrence H. “World War II Poster Campaigns Preaching Frugality to American Consumers.” Journal of Advertising 32 (2003): 72.

The

result of all the demand placed on the industry because of the war brought about

great opportunities for Delmarva poultry growers, processors, and hatcheries. This wartime prosperity also laid the foundation for

long-term expansion. This was

because it was during this time that farmers had the drive to learn how to

produce better chickens in a shorter period of time to meet the demand of the

troops overseas while at the same time making a profit.

This wartime demand also created a shift in the base of Delmarva’s

agricultural economy. Once farmers

had invested in a chicken house and made improvements to it during the war to

meet the demand, they continue to use the chicken house infrastructure even

after the war. As long as was

profitable for them, they would continue to use it.

Also

after the war a number of new firms began to creep up on the peninsula that

aimed at modernizing and revolutionizing the poultry industry.

These firms replaced the older poultry processing businesses of the area,

where the grower assumed most of the risk of poultry growing. In

the years between 1945 and 1965 these new firms were able to produce vertically

integrated companies that oversaw the production of chickens as they went from a

hatched chick to a dressed bird ready for sale.[xxvi]

It was also during this time that markets for commercialized feed

companies were created. This created a greater market for corn and soybean and helped

end the canning industry in the area.

As

automated chicken facilities began to appear in the 1950’s and early 1960’s,

growers had to take on short term financing costs for things such as feed,

medicines, chicks, and other things.

This meant a high risk situation was created for the grower where one bad

batch could make a grower go bankrupt, causing some farmers to be hesitant to

take on the risk of chicken farming. Vertical Integration of poultry helped

remedy this problem.[xxvii]

In

vertical integration of poultry growing it is the integrators that accept most

of the risk of poultry growing. This

is because in accepting the risk they have greater control over the quality of

the bird as well as the quantity. Ownership

of the breeding stock, chicks, and other inputs allows the integrator to develop

breeds of poultry to meet market needs and have control over production

quantities, quality, and costs. In

vertical integration integrators, such as the Perdue company provide growers

with the chicks and feed usually from integrated owned feed mills.

Integrators will often offer veterinary services, medication, part of the

fuel, and field supervisors who oversee operations as well.

This leaves the grower to provide housing, equipment, labor, water, and

part, if not all, of the fuel and the litter.[xxviii]

Well

into the 1950’s most chicken left the processing plants defeathered, drained

of blood, and sometimes with the head and feet removed but not eviscerated. Processing plants at this time were still simplistic and

labor demands remained low. The

process of evisceration, better cleaning of the carcasses, and the use of chain

supermarkets to sell chickens resulted in the construction of new processing

facilities and a much larger demand for workers.

The chicken was sold in a different form which had consequences on both

the labor demands and processing operations.[xxix]

In

the 1970’s several other factors helped play a role in pushing the industry

towards greater profitability. Fast

food chicken emerged with the opening of Kentucky Fried Chicken around 1952,

health concerns popped up about the fat content of red meat some time after

1970, and finally marketing campaigns were being developed by poultry companies

to promote brand loyalty in the 1970’s. The

fast food industry and consumers were creating a demand for chicken to leave the

plant cut into pieces as opposed to gutted broilers.

This called for the establishment of production lines following the

removal of the head, feet, and intestines that cut the carcasses into smaller

pieces and in some cases deboning the chicken.[xxx]

A

new need for labor was created by these new processing facilities because this

process of cutting chicken into pieces could not be mechanized and required more

employees on the line. By the late

1980’s poultry companies became desperate for workers.

With little options poultry companies soon began accepting labor from the

migrant labor force left over from the trucking and canning industries.

The

poultry industry has today become a major source of employment for immigrants.

Poultry firms on Delmarva employed at least 3,200 immigrants in 1996

compromising between 40 and 60 percent of the work forces in processing plants.[xxxi]

Immigrant labor on the Peninsula is not a recent event however; migrant

laborers have been around a longtime.

Migrant

workers first appeared in the truck farming days.

They would come each year from the south and head northward as crops

ripened. Upon arrival they received jobs picking the crops and hauling them to

the canneries and other markets present on the shore at the time. During World

War II these migrant workers helped fill the demand for labor. Many of the shore canneries at this time had a labor shortage

and as a result camps for imported labor were created, while existing camps

expanded. During the war three

camps were set up in Wicomico, four in Worcester, and two in Somerset County.

Some of the camps housed German Prisoners of war.[xxxii]

Farmers may have turned to POW’s for additional labor because tire and gas

rationing in 1942 cut the normal supply of migrant laborers by almost 50

percent.[xxxiii]

While

some labor was being supplied by POW’s in 1942, most of the labor was obtained

from nearby towns. Only 10 percent

of the labor in Maryland was met by migrant laborers in 1942.[xxxiv]

After the war these migrant workers persevered in both the canning and

trucking industries.

In

1958 some 5,455 migrant workers came into the Maryland area.

They would set up camp along the shore often with living conditions

within the camps being poor. Conditions

in the camps often consisted of framed shacks which were only about 8 by 10 ft

cubicles containing cots, small crock stoves and a light bulb.

The camps were overcrowded with laborers who made them their home during

the peak 4 month harvesting season.[xxxv]

Migrant

camps began to diminish in the early 1960’s as a result of the implementation

of stricter health and safety requirements aimed at improving the treacherous

living conditions of the workers. The

most important of these new regulations was the adoption in 1960 of strict

health department codes. These

codes placed regulations on housing and sanitation.

Growers and operators under these new regulations had to meet

requirements in water supply, sewage disposal, pest control, and fire safety.[xxxvi]

Violators were subject to between $25 and $100 fines.

Other factors that also helped push migrant camps out were dry weather

conditions, and replacement of workers by automatic picking equipment.[xxxvii]

In time the many of the migrant camps vanished along with the canneries,

although some still remain today. Migrant

workers persistently appeared in the region even after the fall of the canning

industry and continue here today, primarily working in the poultry industry.

Migrant

workers working in the poultry processing plants of today are more commonly

referred to as immigrants. Migrant

worker is a term applied to the seasonal workers who provide work during the

growing season. Migrant workers are

only temporarily in an area and migrate from the south northward as crops ripen

during the peak growing season. Immigrant

workers are different in that they have migrated to an area and stay there

permanently. Many of the workers in

processing plants are immigrant workers. They work year round in the poultry processing plants.

Therefore, there was a shift as the canning industry disappeared on the

peninsula where some of the migrant workers got year round jobs in the poultry

processing plants and transformed into immigrant workers.

These workers have become an essential part of the poultry industry on

the peninsula providing a labor force that would otherwise be unavailable.

The

demand for work being met by immigrant populations has created an environment

where laws are not always so carefully considered, thus creating worry for the

citizens of the region. Many

problems are associated with the influx of immigrant workers on the peninsula,

including, driving without a license, drugs, theft, housing issues, and property

value decline.[xxxviii]

An

identity crisis as a result of identification fraud and multiple identities has

arisen on the peninsula that is linked to immigrants desperate for work in an

industry desperate for workers. In

order to be hired in the chicken plants of Delaware, Eastern Maryland, and

Virginia a valid name is needed. Giving

faulty names has a major impact on tax returns, medical care, pensions, and

criminal cases. Faulty names have

been reported in jail, police barracks, infectious disease reports, and

maternity wards.[xxxix]

The

influx of immigrants has also created a rental market that is competitive as

well as profitable for those in real estate, but this too has created problems.

In many of the cases rented houses are barely habitable and are being

rented for $1,200 to $1,500 a month.[xl]

Overcrowding of these houses has become common.

One place in Georgetown, Delaware experienced difficulty with a propane

leak causing fire fighters to be alarmed when as many as 30 people living in the

three story house came out. Most of

the Guatemalans that have flocked to this Georgetown community work double

shifts leaving work at one plant and starting a shift at another plant.

Their lives revolve around working leaving little time for recreational

activity, so luxurious living accommodations are unnecessary and unwanted.[xli]

Often for communities like Georgetown it has been difficult for long-time residents to become accustomed to these newcomers in their communities. Tensions have grown between natives of these often tradition bound towns and the immigrants who seem unaccustomed to the ways of these communities.[xlii] In the case of Georgetown some of the Guatemalans have confused private homes for public parks and scared local residents when spotted taking pictures in their front lawns. Also private pools have been mistaken for public pools and some residents have come home to find them swimming in their pools.[xliii]

An adjustment has to be made by these poultry dependent communities, where immigrants need to adjust to their new surroundings, and native residents have to be willing let go of past traditions and adjust to ongoing changes within their communities. It is important for communities such as Georgetown to realize the important role that the immigrants play in the local chicken industry. These immigrants are the only ones willing to do the work that goes into producing the chickens and without them the chicken industry would be devastated. Loss of immigrant labor would mean that communities such as Georgetown would lose much of the money the chicken industry brings and circulates throughout their small town. While it may be hard for them to adjust to the influx of immigrants, they have to realize these immigrants are playing a vital role in their community and are just the latest in generations of migrant workers on the shore.

The

government is having trouble controlling the flow of illegal immigrants to food

and agriculture companies. This is partially due to complaints being received by

civil rights officials and politicians claiming harassment of Mexicans and

others from Central America. These

complaints are the result of an outrage caused by federal raids on meatpacking

plants that have sent many illegal workers home.[xliv]

The

Delmarva Poultry industry gets credit from federal officials for their

willingness to help combat against the hiring of illegal immigrants. Many of the plants have an open door policy with the INS

where they allow the INS to come in at anytime unannounced to make sure all

their employees have the right working papers and valid identification.

This is a good way for them to counter the hiring of undocumented

workers. The reason that poultry

companies have difficulty with hiring illegal immigrants is because they teeter

on a thin legal line, where the law has created a loophole.

Poultry companies cannot challenge a potential employee that produces

what appears to be legitimate identification.

If they challenge a potential worker that presents a legitimate

identification, they can be liable by asking too much.

Perdue, one of the regions largest employers in 1997, was cited by the

Department of Justice. They were

charged with violating the civil rights of a

worker because they asked her to obtain a new alien registration card as

her old one showed her maiden name. The

company was required to pay a fine of $2,300 and had to pay the worker $2,046. [xlv]

The

average number of detainees, has tripled to 21,000 a day in the U.S. making it

among the fastest growing portion of the nations prison population. Detainees are illegal immigrants being held by the government

for deportation. In Wicomico

County, detention centers are profiting from this fact with the handling of INS

detainees. The U.S. Immigration and

Naturalization Service pays $50 a day for a jail bed. A bed costs only $17.89 to provide in Wicomico County,

meaning a $32.11 profit is gained. In

1999 the Wicomico County Detention Center made $2.7 million from the handling of

approximately 84,000 INS detainees, which was equivalent to two thirds of the

money they took in. The detention

center is constantly operating at its full capacity of 655 inmates.

The jails are experiencing an influx after the passing of new immigration

laws by Congress in 1996 requiring foreigners that face deportation to be jailed

while they await verdicts on their fate. Those

being held include immigrants with criminal records and expired visas.[xlvi]

Tyson

foods was recently indicted in December 2001 on the charges of conspiring to

smuggle illegal immigrants to work at various processing plants in Tennessee,

Virginia, North Carolina, and Arkansas. The

government charged the company and six of its employees with helping immigrants

to get across the Mexican border and aiding them in getting counterfeit work

papers. This case is just one

example of the dependence of poultry companies on foreign workers and has been

used to argue against cracking down on the hiring of illegal immigrants.

This is due to the potential impact it could have on the nations food

industry. Companies such as Tyson

may use immigrants because they can profit by paying low wages and pushing

production lines faster with the threat of sending them back. Also, in many

cases these workers are much more willing to endure the hazardous conditions of

meat processing plants.[xlvii]

As

stated before efficiency is the key, in modern processing plants, to successful

poultry production. The main goal

shared throughout all processing plants is fast processing because the amount

earned per chicken depends on the volume and speed of the plant and how well its

workers adjust to both. Sixty

million pounds of chicken are processed at plants on the Peninsula every week

and companies in need of workers have added extra shifts and extra work days to

deal with the shortage of workers. All

tasks in a processing plant are balanced to the second with each worker almost

being part of a machine. The

dangers created by such demands and emphasis on efficiency explain the shortages

of workers in such an demanding field of work.[xlviii]

There

are few places as dangerous as a poultry processing plant.

Poultry workers make less money compared to other manufacturers and are

injured at twice the rate. One out

of six poultry workers suffers from work related injuries or illness every year.

One of the most common injuries today is what is known as “neighbor

cuts,” due to overcrowding and workers unintentionally cutting the person next

to them. The processing plants are also challenging to the body’s

senses. In the slaughterhouses the

temperatures can range between 28°

in a room for packages waiting to be shipped, to a 120°

scalder where feathers are loosened. During

the summer season the plant can get so hot that chickens being hung can

suffocate in less than one minute. Also

adding to the dangers of these plants are the slick conditions created by fat

and blood dripping from the gutted chickens.

Labor unions and government agencies monitor companies efforts to prevent

injury but only about 40% of processing lines on Delmarva have union

representation.[xlix]

It is difficult to say what will become of the issues surrounding the poultry industry and its immigrant labor force. Technology has been unable to find a better alternative to the precision of the human hands and with conditions remaining as they are today in the plants, it is unlikely poultry companies will succeed in finding an alternative labor force. Even the system of migrant workers continued to persevere after their initial source of work in the trucking and canning factories was lost, in the form of immigrant labor. Loss of work in the poultry industry therefore may not be effective in pushing immigrants out of the area. These immigrants may continue to find jobs in other forms of work.

This

is not to say however that all of the work being done in poultry processing

plants on Delmarva is provided by immigrant workers.

For example, Salisbury’s processing plant run by the Perdue company on

U.S. Route 50 is located in a predominately black neighborhood. The company does not keep written record of the race of its

employees but predominately the workers have been African American.

As stated earlier many of the workers in the processing plants on the

Delmarva Peninsula after World War II shifted from white female workers to black

male workers.[l]

Many of these workers continue to work in the processing plants on the Peninsula

today.

Cheap

labor is just one example of how poultry companies have been able to externalize

much of the costs of production. By

externalizing the costs of production poultry companies are able to continue to

provide consumers with cheap food. Consumers

may feel that they benefit from cheap food such as chicken but fail to realize

that they pay in terms of lost tax revenue and increased social and

environmental costs. As communities

on the peninsula like Salisbury work as a periphery providing chicken to serve

metropolises like Philadelphia and New York, they take on the environmental

burden placed by such industries. Not

only do communities on the peninsula take on the environmental burden but the

social burden of cheap labor as well.

Over

the past eight decades the Delmarva Peninsula has gone through a major change

with the continued expansion of the poultry industry over the years. It is true that the birth of the poultry industry is a great

success story for our region, but one that is not without its problems. Whether

Delmarva growers will be able to overcome their obstacles is difficult to

determine, but the future is likely to be filled with immigration and

environmental disputes. Poultry

growers and companies of the future will have to overcome obstacles such as land

development, competition over markets, environmental degradation and labor

issues in order to maintain the legacy of the industry created by Cecile Steel.

Wicomico

County Broiler Production Statistics

|

Census

Year |

#

of Broilers Produced |

Value

of Sales |

|

1929 |

NA |

$174,190 |

|

1939 |

NA |

$496,140 |

|

1949 |

NA |

$8,132,126 |

|

1959 |

NA |

$16,248307 |

|

1969 |

NA |

NA |

|

1978 |

NA |

$64,033,579 |

|

1987 |

72,732,532 |

$116,189,000 |

|

1997 |

76,432,601 |

$154,348,000 |

Information provided by Maryland Agricultural Statistics Service U.S. Department of Agriculture.

[i] Seybold, Kimberly. “The Delmarva Broiler Industry and WW II: A Case in Wartime Economy.” Delaware History 25 (1993): 200-210.

[ii] Williams, William H. Delmarva’s Chicken Industry: 75 Years of Progress. Delaware: Delmarva Poultry Industry,Inc, 1998.

[iii] Williams, 15.

[iv] Williams, William. Personal interview. 21 April 2004. Sprows, Amanda. Delaware Technical Institute. Tape on File at Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Salisbury State University, Salisbury, Md.

[v] Williams, William. Personal interview. 21 April 2004. Sprows, Amanda. Delaware Technical Institute. Tape on File at Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Salisbury State University, Salisbury, Md.

[vi] Williams, 10.

[vii] Seybold, Kimberly. “The Delmarva Broiler Industry and WW II: A Case in Wartime Economy.” Delaware History 25 (1993): 200-210

[viii] Williams, William H. Delmarva’s Chicken Industry: 75 Years of Progress. Delaware: Delmarva Poultry Industry, Inc, 1998.

[ix] Seybold, Kimberly. “The Delmarva Broiler Industry and WW II: A Case in Wartime Economy.” Delaware History 25 (1993): 200-210

[x] Hartline, Jesse. Interview with Jane King. Email interview. Interview on file at Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Salisbury State University, Salisbury, Md.

[xi] Williams, William. Personal interview. 21 April 2004. Sprows, Amanda. Delaware Technical Institute. Tape on File at Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Salisbury State University, Salisbury, Md.

[xii] Williams, 21-22.

[xiii] Seybold, Kimberly. “Chicken House Apartments.” Delaware History 25 (199): 253-260.

[xiv] Williams, 28.

[xv] Seybold, Kimberly. “The Delmarva Broiler Industry and WW II: A Case in Wartime Economy.” Delaware History 25 (1993): 200-210

[xvi] Williams, William H. Delmarva’s Chicken Industry: 75 Years of Progress. Delaware: Delmarva Poultry Industry, Inc, 1998.

[xvii] Williams, 32-33.

[xviii] Williams, William. Personal interview. 21 April 2004. Sprows, Amanda. Delaware Technical Institute. Tape on File at Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Salisbury State University, Salisbury, Md.

[xix] Williams, 20.

[xx] Truitt, Charles J. Historic Salisbury Updated 1662-1982. Maryland: Historical Books Inc., 1982.

[xxi] Williams, 35.

[xxii] Witkowski, Terrence H. “World War II Poster Campaigns Preaching Frugality to American Consumers.” Journal of Advertising 32 (2003): 62-82.

[xxiii] Seybold, Kimberly. “The Delmarva Broiler Industry and WW II: A Case in Wartime Economy.” Delaware History 25 (1993): 200-210

[xxiv] United States Department of Agriculture. National Agricultural Statistics Service. Broiler Industry Structure. Washington, DC: 2002.

[xxv] Williams, William. Personal interview. 21 April 2004. Sprows, Amanda. Delaware Technical Institute. Tape on File at Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Salisbury State University, Salisbury, Md.

[xxvi] Miller, Mark J., and Roger Horowitz. “Immigrants in the Delmarva Poultry Processing Industry: The Changing Face of Georgetown, Delaware.” JSRI Research and Publications Occasional Paper Sources. 17 Dec. 2004 <http://www.jsri.msu.edu/Rands/research/ops/oc37.html>

[xxvii] Ollinger, Michael, James McDonald, and Milton Madison. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Structural Change in U.S. Chicken and Turkey Slaughter. Agricultural Economic Report Number 787.

[xxviii] Ollinger, Michael, James McDonald, and Milton Madison, 11.

[xxix] Miller, Mark J., and Roger Horowitz. “Immigrants in the Delmarva Poultry Processing Industry: The Changing

Face of Georgetown, Delaware.” JSRI Research and Publications Occasional Paper Sources. 17 Dec. 2004. <http://www.jsri.msu.edu/Rands/research/ops/oc37.html>

[xxx] Miller, Mark J., and Roger Horowitz. “Immigrants in the Delmarva Poultry Processing Industry: The Changing

Face of Georgetown, Delaware.” JSRI Research and Publications Occasional Paper Sources. 17 Dec. 2004 <http://www.jsri.msu.edu/Rands/research/ops/oc37.html>

[xxxi] Miller, Mark J., and Roger Horowitz. “Immigrants in the Delmarva Poultry Processing Industry: The Changing

Face of Georgetown, Delaware.” JSRI Research and Publications Occasional Paper Sources. 17 Dec. 2004 <http://www.jsri.msu.edu/Rands/research/ops/oc37.html>

[xxxii] Truitt, Charles J. Historic Salisbury Updated 1662-1982. Maryland: Historical Books Inc., 1982.

[xxxiii] “Farmers Told to Seek Labor.” Salisbury Times 26 May 1942, evening ed.: 1.

[xxxiv] “Nearby Towns Supply Labor for Farmers.” Salisbury Times 25 May 1942: 8.

[xxxv] Shern, Laurence. “Maryland’s Migrants Hit Hard by Bad Weather.” The Washington Post 16 Aug. 1959.

[xxxvi] Clopton, Willard. “The Pickin’s Are Easier for Migratory Workers.” The Washington Post 19 July 1964.

[xxxvii] Clopton, Willard. “The Pickin’s Are Easier for Migratory Workers.” The Washington Post 19 July 1964.

[xxxviii] Miller, Mark J., and Roger Horowitz. “Immigrants in the Delmarva Poultry Processing Industry: The Changing Face of Georgetown, Delaware.” JSRI Research and Publications Occasional Paper Sources. 17 Dec. 2004 <http://www.jsri.msu.edu/Rands/research/ops/oc37.html>

[xxxix] Escobar, Gabriel. “Workers Answer to Multiple Names, Culture Fraud Flourishes in Delmarva Chicken Town.” The Washington Post 30 Nov. 1999, A01.

[xl] Escobar, Gabriel. “Immigration Transforms a Community, Influx of Latino Workers Creates Culture Clash in Delaware Town.” The Washington Post 29 Nov. 1999, A01.

[xli] Escobar, Gabriel. “Immigration Transforms a Community, Influx of Latino Workers Creates Culture Clash in Delaware Town.” The Washington Post 29 Nov. 1999, A01.

[xlii] Miller, Mark J., and Roger Horowitz. “Immigrants in the Delmarva Poultry Processing Industry: The Changing Face of Georgetown, Delaware.” JSRI Research and Publications Occasional Paper Sources. 17 Dec. 2004 <http://www.jsri.msu.edu/Rands/research/ops/oc37.html>

[xliii] Escobar, A01.

[xliv] Barboza, David. “Meatpackers’ Profits Hinge on Pool of Immigrant Labor.” The New York Times 21 Dec. 2001, late ed.:A26.

[xlv] Escobar, Gabriel. “Workers Answer to Multiple Names, Culture Fraud Flourishes in Delmarva Chicken Town.” The Washington Post 30 Nov. 1999, A01.

[xlvi] Montgomery, Lori. “Rural Jails INS Detainees.” The Washington Post 24 Nov., A01.

[xlvii] Barboza, David. “Meatpackers’ Profits Hinge on Pool of Immigrant Labor.” The New York Times 21 Dec. 2001, late ed.:A26.

[xlviii] Sun, Lena H., and Gabriel Escobar. “On Chickens Front Line; High Volume and Repetition Test Workers Endurance.” The Washington Post 28 Nov. 1999, A01.

[xlix] Sun, Lena H., and Gabriel Escobar. “On Chickens Front Line; High Volume and Repetition Test Workers Endurance.” The Washington Post 28 Nov. 1999, A01.

[l] Williams, William. Personal interview. 21 April 2004. Sprows, Amanda. Delaware Technical Institute. Tape on File at Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Salisbury State University, Salisbury, Md.