Chapter Two:

Agriculture in Wicomico County prior to 1880

Elsbeth Mantler

In 1880 John H. Horseman owned a farm in Barren Creek, the most northwestern corner of Wicomico County. This area is most recognized today by the name of its main community, Mardela Springs, situated directly on Highway 50 that runs from Washington D.C, across the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and as far east as Ocean City. The Barren Creek region borders Dorchester County to its west, the city of Salisbury to its southeast, and the southern portion of Delaware to its east. In 1680 Horseman’s family first broached the eastern shore of Maryland, and his descendents continue to live in the area today. In 1880 he owned about 150 acres of land, 80 of which consisted of improved tilled land and 50 of which were woodlands and forest. The value of his land, fences and buildings totaled approximately $1,000, while the value of all of his machinery was twenty dollars (to put this in perspective, in 1880 a night at the opera cost one dollar, according to newspaper ads).[i] In 1879 Horseman reported that he did not spend any money on the purchase of fertilizer, which means he was probably using manure from his livestock, or fish carcasses to garnish his land. His main crop, for which he reported used eighty acres of his land, was “Indian” corn. In small amounts he also farmed wheat, potatoes, sweet potatoes, livestock and poultry, all of which were probably for his own personal subsistence.[ii]

At the same time, on the eastern border of Salisbury near Parsonsburg, a man named Jacob C. Phillips was farming. He was 41 years old, and had a farm of a comparable size to Farmer Horseman’s at 175 acres. Yet, the farming on Farmer Phillips’ farm was relatively distinct from Horseman’s. Horseman grew corn, which was a popular export crop in the area as a whole, but did not report growing any fruit. Orchard fruits such as apples, pears, and peaches were also locally common in 1880. In 1880 Phillips reported cultivating 200 apple trees and 2,000 peach trees. He exported 100 bushels of apples and 700 bushels of peaches in a single year. In addition to fruit, Phillips also grew wheat, producing nearly 100 bushels in that same year.[iii] All of his fruit and wheat was sold in distant commercial markets.

The 1880 Agricultural schedule of the US Census did not include a category to record berries grown on farms, whether strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, cranberries, or blueberries. Although not mentioned in either Phillips’ or Horseman’s records from 1880, or any other Wicomico County farmers, commercial berry production was widespread throughout the Lower Eastern Shore. From numerous newspaper and magazine articles in the 1870s and 1880s, it is clear that berries were being grown for export throughout Delaware and Maryland. As the New York Times stated in one of the earliest articles about local berries: “From the Berlin and Snow Hill, and Pocomoke and Wicomico Railroads there were shipped in 1872 219,450 quarts of cultivated berries, and 3,046 buckets of wild berries, and in 1873 there were shipped of cultivated berries 690,550 quarts and 1,500 buckets of wild berries.” [iv]

Men

Working in Strawberry Field in Fairmount, Somerset County, 1897. (From: Somerset

County: A Pictorial History. Stump, Brice Neal. Donning, Norfolk, 1985, p.

62.)

Through studying farmers such as John Horseman and Jacob Phillips, as well as the literature of that period, it is evident that the main crops being grown on the peninsula in 1880 were corn, wheat, orchard fruits and berries. Further, agriculture was the dominant profession on the shore. In the 1880 census there 1,701 farms in Wicomico County, which had a total population of only 18,016 people.[v] Crops grown in Wicomico County reached markets throughout the East Coast – this small county supplied food to Philadelphia, New York City, Baltimore, and even Boston. By 1880, Phillips, Horseman, and other Wicomico County farmers were using the railroad and river to send out their crops to metropolitan areas, living in a newly established county that would support their economic goals, and farming almost solely for the purpose of exporting their goods to urban areas in the mid-Atlantic region. As such, these farmers participated in a mode of agriculture that shares many similarities both with the farmers that preceded them, and Wicomico County farmers of today.

Wicomico County as Periphery

Wicomico County comprises the Lower Eastern Shore along with Worcester and Somerset Counties. Along the eastern shore in 1880 and prior, there were no cities in which one would have regarded as a booming industrial center or even a metropolitan area. Yet, in Wicomico County farmers like Jacob Phillips were growing 700 bushels of peaches, and almost 700,000 bushels of berries were being shipped out of Snow Hill in one year. Evidently these numbers show that farmers in the county were not growing for themselves in most cases, nor were they growing for proximate farmers’ markets. Instead, these farmers were growing these crops in order to send them off to larger, more urban areas, namely New York and Philadelphia.[vi] The majority of farmers on the Lower Eastern Shore were growing a surplus of crops, in other words more than the people in their own area could consume. This is where cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Wilmington, among others come into the agricultural picture.

William Cronon

explains a dichotomy that exists between areas such as Wicomico County,

peripheries, and areas that are at its roots urban, metropolises, such as

Philadelphia. The relationship between the periphery and the metropolis is

reciprocal— one cannot exist without the other. In short, the periphery areas

produce a surplus of agricultural products and the metropolis provides a market

for the excess of crops. Cronon explains, “A rural landscape which omits the

city and an urban landscape which omits the country are radically incomplete as

portraits of their shared world… [there are] underlying market principles that

have linked city with country to turn a natural landscape into a spatial

economy.”[vii]

Wicomico County in 1880 fell directly into the role of a periphery. The farmers

in the area were producing exponentially more than they could consume, but not

without due purpose. They were cultivating all of these crops in order to sell

to metropolises nearby. In turn the urban areas such as New York and

Philadelphia were providing them with the financial motivation to grow these

crops for their markets. The area was used so much for the purpose of exporting

crops that in some cases the Eastern Shore of Maryland was identified directly

and singularly with providing for its surrounding cities and not for much else.

In an article titled, “The Eastern Shore of Maryland” in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine printed in August of 1888, the

peninsula was referred to as, “a tributary to Philadelphia.”[viii]

Probably many observers during the time only recognized the Lower Eastern Shore

as a provider for more populated, urban areas.

A

Brief Introduction to the Lower Eastern Shore of Maryland

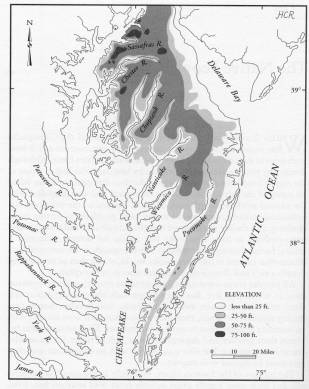

While in the Lower Eastern Shore a person could literally walk in a straight line and very soon would come into face to face contact with one of the many bodies of water running through or near it. The peninsula is surrounded by the Chesapeake Bay to its west and the Atlantic Ocean and Delaware Bay to its east, not to mention the web of streams and tributaries that flow to and from these larger bodies of water, circumnavigating Somerset, Worcester, and Wicomico Counties.[ix] The proximity to all of this water affects the environment of the peninsula, causing it have a very moderate climate. Its mild winter with little snow and average temperatures around 40 degrees Fahrenheit is largely due to the peninsula’s insulation by its surrounding waters. The summers are also mild with an average temperature of 75 degrees.[x]

Eastern

Shore Topography (From: Eastern Shore

Indians of Virginia and Maryland. Rountree, Helen C. and Thomas E. Davidson,

University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, 1997, p. 2.)

This moderate climate is very conducive to farming. Some sensitive plants can die from just one exposure to frost, but on the Lower Eastern Shore the problem of frost is averted. On average the area receives up to 200 frost free days which makes for a very long growing season. In many cases farmers in this area are able to begin their season 2 to 3 weeks earlier than their northern competitors.[xi] In fact, the area was known for its early season and was favored to markets because they could get crops such as Strawberries to market by May 1st opposed to other agricultural regions which would produce weeks later.[xii]

This mild climate would sound like a paradise to some but there is one stipulation— the rain. On the Lower Eastern Shore the average rainfall per year is approximately 40 to 45 inches. These numbers are very good for supporting crops, just not optimal for taking a stroll outside. Usually farms need a minimum of about 20 inches of rain per year in order to survive; this is farms without any sort of artificial irrigation. Thirty inches of rain in most areas is more than satisfactory. But, the abundance of rainfall in the area is not a problem due to the soil and the rainfall patterns. The rainfall is spread evenly throughout the year, so it is not as if one season is overwhelmed with rain, and crops have the potential of being flooded.[xiii] In addition, the soil on the Lower Eastern Shore is very sandy which would be logical being that, geographically speaking, the land between the ocean and the bay is comprised of old sand dunes. Since the soil is very sandy it does not retain water very well, working to the farmer’s advantage. The heavy rainfall and the non-absorbing sand work hand and hand to provide a very supportive environment for the growth of plants.[xiv] This is not to say that the Lower Eastern Shore is a farmer’s utopia, a perfect paradise for growing, but in comparison to most other places it is very close.

A History of Agriculture on the Lower Eastern Shore

The first thing that was exported out of the Lower Eastern Shore was not actually a plant that springs out of the ground, but rather the hide of an animal, the beaver pelt. Englishmen in the 1620’s and 30’s decided that the Chesapeake Bay and the Eastern Shore of Maryland were valuable, and important places to establish trade. The Bay and the many streams around the peninsula made contact with the Indians very readily available by boat. At this time the Dutch were already trading with the Indian groups along the Delaware Bay, so the English probably took their chance on profiting on the pelts found on the coast of the Chesapeake.[xv] John Westlock was the first recorded settler who had contact with the Native Americans on the Eastern Shore of Maryland and that was with the Manokin Indians in what is today Somerset County. The main trading post for the beaver pelt was at Kent Island which is today at the foot of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. However, fur never was as large scale as tobacco in this particular region. The profits as a whole were not as large as those gained with the sale of tobacco. Men involved in the fur trade did make out very well, only because there were very few of them to split the profits between.

Tobacco began on the peninsula as a very profitable crop. In many cases tobacco was so prevalent that at times it was even used as a currency.[xvi] It was cultivated by the settlers with a slash and burn technique in order to grow the crop in mass quantities. First, the farmers would cut the bark off of the trees in the area they wished to farm in order to kill it. Then, they would burn the ground in order to do away with any debris or plant life on the earth’s floor. After that the soil would be piled into one foot tall hills in which the crop could be planted in. Tobacco could be cultivated from these lands for about 4-5 years, after that the plots would be abandoned; they would be plowed, but not seeded in hope that the land would become replenished in about 20 years.[xvii]

This method did not last very long on the eastern coast of the Chesapeake Bay. The Lower Eastern Shore was not as well suited for tobacco growth as it was for other products such as corn or wheat. The soil on the Lower Eastern Shore was almost too beach-like for the tobacco plants sustentation. As Lois Green Carr explains, “There was much less prime tobacco soil and more tidal marsh and beach in Somerset [part of the Lower Eastern Shore] than in most parts of the Chesapeake tidewater…only a fifth of present Somerset soil could ever produce high yields of tobacco and that quality was generally low.”[xviii] According to Carr about 29% of the land on Lower Eastern Shore was suitable to grow tobacco, out of that 11% suitable for high yield, opposed to wheat in which almost 75% of the land was suitable, and corn in which almost 83% suitable.[xix] It is likely that to many, growing tobacco in this area simply did not make sense when it was apt to growing other crops more efficiently.

At this point the main crop base of the peninsula changed from tobacco to the export crops of corn and wheat. Primarily, wheat was used as a distant export. It was the main crop that was bringing money into the shore after tobacco had its fall. The Europeans liked wheat; they had grown it traditionally in their country and were able to receive it in abundance from America. In the late 1600’s markets for wheat expanded tremendously. Both crop failures in southern Europe during the mid 1600’s and relaxed British importing regulations allowed wheat to be sent to England where it was in need. [xx]

Corn, on the other hand, was more of a local market crop. Europeans had not acquired a taste for corn meal, which was the main use of the Indian Corn grown in the area. In many cases it was the only feed given to slaves and lower class workers. Farmers could grow it easily and abundantly and sell it off cheaply to the people who had no other choice but to eat it. In most cases of plantations and farms corn was what the slaves would have been fed. As unlikely as international trade of corn was from the shore, there were instances of selling of corn to slaves in other countries. It was recorded that planters of the Lower Eastern Shore were at one point providing corn to the British West Indies, where slave labor was highly used for the large-scale cultivation of sugar crops. [xxi]

During the 18th century other products became popular for the farmers in the area. Beans, peas, oats, buckwheat, barley, and rye were being grown in small amounts all over the peninsula. Lumber planks and shingles began to appear more regularly on inventory lists.[xxii] The crop diversification that was taking shape at this time was very good for the economy. Instead of a bulk of the population relying on one crop for the whole groups’ welfare, they now had many different crops and crafts to share the burden. As the network between all involved in the farming business got larger, so did the lack of chance that everyone in the farming business could perish due to an unsuccessful season of one crop.[xxiii]

In order for this diversified market to really take shape much labor was required. In most cases on the Lower Eastern Shore slave labor was used on the farms prior to the Civil War. In 1850 there were a total of 2,903 farms on the Lower Eastern Shore, and 9,032 slaves.[xxiv] One could speculate that at least a hand full of slaves could have been on every farm, or that some farms had more than others, either way farming in this particular area was without a doubt involved in slavery.

After the Civil War many things about farming in the area changed. In 1850 there were 252,537 acres of improved farmland, in the Lower Eastern Shore, which at the time consisted of Worcester and Somerset counties (Wicomico County politically did not exist yet).[xxv] Ten years later the number of acres of improved farmland increased to 274,482.[xxvi] In 1870, after the Civil War, the now three counties of the same Lower Eastern Shore showed a slight decrease in the number of acres of land which were being used for farmland- 268,195 acres.[xxvii] It was not until 1880 that the impact of the slaves on the land was most noticeable. By 1880 the number of acres of improved farm land had dropped to 211,054. [xxviii] It is quite possible that by losing all of the labor that was found in slavery the area was simply not able to keep up as much land.

Looking at the sheer number of farms in the area, we can hypothesize the impact of slavery on the agriculture. Intriguingly, the number of farms on the Lower Eastern Shore did not decrease after the War, rather they increased. In 1850 there were 2,803 farms in total, in 1860, 2,775.[xxix] After the war in 1870, there were 3465 farms, and most drastically in 1880 there were a total of 4,777 in the three counties that now composed the Lower Eastern Shore.[xxx] In knowing that the actual amount of land which was being taken up by farming decreased heavily and the number of farms increased, it is probable that the farms were becoming smaller, largely due to lack of available cheap or free labor that was being denied to most farmers. It could have been harder for the planters to maintain plantations that were 500 acres and larger now that the slaves were not there to provide a free means of up keeping the land and crops.

The population of African Americans did not decrease after the Civil War— the slaves were probably not leaving. Rather, it could be postulated that they stayed on the shore and contributed to the economy. In 1850 the total number of slaves and free blacks was 15,529.[xxxi] Ten years later the population slightly increased to 16,879, and by 1870 had reached a total of 17,549.[xxxii] In 1880 the population of blacks in the three counties was up to 20,784, 5,000 more African American people were living in the area.[xxxiii] They could have possibly been free, now contributing to the agricultural economy on smaller farms. Within 30 years the population of blacks grew by almost 25 percent, only slightly lower than the growth of the white population of 30 percent.[xxxiv] It is possible that most blacks in the area were not leaving to go north or west; instead they were probably staying in Wicomico County and its surrounding areas, possibly contributing to the farm and industrial life on the peninsula.

As in the 1700’s and 1800’s there was much transition after the time of slavery which changed the face of agriculture for the area. Before the Civil War the government had no involvement in agriculture or the environment and many new technologies had not yet been invented. In addition Wicomico County had not even been established yet. All of these things, though more modern than the stepping stones of fur, tobacco, wheat, corn, and slavery also helped to place Horseman and Phillips in their positions in 1880.

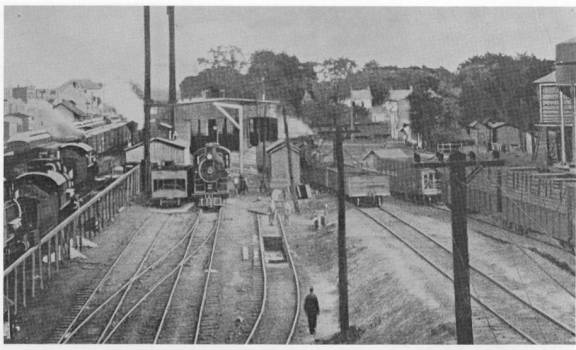

A Railroad, a River, and a New County

On Independence Day, 1860, the Eastern Shore Railroad took its maiden voyage in Salisbury. The emergence of the railroad was critical to the economic strength of the area because, “Up to that time all community activity was centered around wharves and docks...the economic life was based on the facilities of a narrow shallow river that meandered out of the Chesapeake Bay and points beyond.”[xxxv] The railroad meant that the farmers in the area were no longer confined to depending on the shallow Wicomico River, or the distant Nanticoke River which did not run in the middle of Salisbury like the Wicomico, but rather was on its northern border. It brought in new businesses to Salisbury; lumber companies such as the Jackson Brothers and E.S. Adkins Company soon had large mills in the area. [xxxvi] They were able to ship goods to Philadelphia, Baltimore and New York with much more ease than in times prior to the arrival of the ‘iron horse’. The railroad made contact between the surrounding urban areas of the peninsula much more accessible to the residents on the shore.

Railroad

in Delmar, 1899 (From: Wicomico County

History. Corddy, George H., Peninsula,

Salisbury, 1981, p. 82.)

Before 1860 the only way for planters to get their products anywhere was by boat or wagon. Early on, the Wicomico River was not very practical for this use. The river was very shallow and narrow in many places and was sometimes impassable for ships. In order for Salisbury to become the port that it longed to be something about the river needed to be done. Local efforts began by the citizens of Salisbury attempting to construct dykes for the improvement of the river. The community spent over $25,000, but that was not enough to open the river to larger boats. [xxxvii] In 1872 the first attempts at publicly dredging the river began due to cooperation between the city and the United States Army Corps of Engineers. One of the proposals by R.L. Hoxie, Lieutenant Colonel of the US Army Corps of Engineers, stated,

“Salisbury contains about 6,000 inhabitants and is a station for two railroads, the New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk, and the Baltimore, Chesapeake and Atlantic, the latter continuing steamboat service to Baltimore. The commerce in domestic, but some of the products may indirectly find their way to foreign parts through Baltimore, Norfolk, Philadelphia, and New York. It contains a shipyard and marine railway where about 100 vessels, ranging from the smallest 125 tons, are repaired annually…The larger vessels draw from 6.5 to 10 feet, a few of them lightering cargo to Salisbury from below the mouth of the river…Salisbury is a town of increasing importance with a present and prospective commerce of considerable value. The cost of restoring, extending, and marinating the …channel will not be excessive and the citizens have contributed freely to the improvement of the river”

Man

using a skiff in pre-dredged Wicomico (From: The

Postcard History Series: Salisbury Maryland, Jacob, John E., Arcadia,

Charleston, 1998, p.1)

This is one of the first instances of government intervention on an issue that dealt with agriculture or the environment in Wicomico County. By endorsing the dredging the government took the control from the private sector, which were running the railroads, and made the river communal. The project was one in which they hoped that the whole community could benefit from. By expanding the river they were hoping to bring prosperity and profit into an area that they thought had the ability to grow. Not only was the infrastructure probably too expensive for private sectors, the government wanted to have control over it so that the benefits would fall among the many and not the few. The original dredging called for a channel seven feet deep and seventy-five feet wide. This width was increased to 100 feet, and by 1885 at the cost of $50,000 to the government the first dredging was completed. [xxxviii]

The

Wicomico River Post-Dredging, 1903, (From: Salisbury

and Wicomico County: A Pictorial History. Jacobs, John E. Donning, Virginia

Beach, 1981, p. 57.)

Both the railroad and the dredging of the river were making Salisbury more metropolitan everyday. Nonetheless, the city was having problems because at the time it was straddling the two counties which made up the Lower Eastern Shore, Worcester and Somerset. Many complications and inconveniences were present because of the splitting of the city between the two counties. As far as voting and politics many people had to go out of their way to involved. It also made any sort of expansion for the area nearly impossible.[xxxix] Residents in the area were concerned with the future of the town. It was very difficult to foresee future progression if the town did not even have physical space to expand. Consequently, in 1867 Salisbury found itself in the middle of the new county, Wicomico.

All of these progressions made in the area in the short amount of time between the Civil War and 1880 led to Horseman and Phillips’ farms, and their acting in the drama that is the periphery, metropolis relationship. The railroad and the dredging of the river allowed the men a plethora of opportunities to export their crops to the metropolitan areas in mid-Atlantic America. These, at the time, modern day improvements, were just a small component of all of the factors that allowed Horseman and Phillips to farm in the way that they did. The demand for fruits, corn, and wheat in places like Philadelphia permitted the men to grow an amount of crops that would yield them enough profit to live.

John Horseman and Jacob Phillips were both farming on the brink of a new century, a time in which many changes in Wicomico County were still to come; like the 19th century and the centuries before it, the future years would bring drastic changes in concern with labor forces, technologies, demands and more. All of these factors, these changes that occur contribute to the Lower Eastern Shore’s function as a supplier of raw goods to urban markets. It is quite possible that Horseman’s descendents could have maintained involvement in the farming of the area and participated in truck farming. Phillips family could have easily jumped on the broiler industry bandwagon, or possibly dabbled in the cannery business. Whatever happened to the two farmers after 1880, it is very feasible that they, and farmers like them, continued to work to fuel the fire that allowed farmers on the Lower Eastern Shore to produce an abundant amount of crops annually. They continued to support the role of Wicomico County as a periphery to markets such as Philadelphia and New York, planting, ultimately, solely to provide.

[i] The New York Times, March 4, 1880 p.7.

[ii] 1880 Agricultural Schedule of the US Census, MD. US Census Bureau. http://209.116.251.240/msaref03/msa_sc_5458_000045_000034/m5175/html/m5175_0542.html.

[iii] 1880 Agricultural Schedule of the US Census, MD. US Census Bureau. http://209.116.251.240/msaref03/msa_sc_5458_000045_000034/m5175/html/m5175_0659.html

[iv] Anonymous. “Delaware Fruit Crops” New York Times (April 11, 1874): p. 4.

[v] 1880 US Census. United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 13 April 2004.

[vi] Anonymous. “Delaware Fruit Crops” New York Times (April 11, 1874): p. 4.

[vii] Cronon, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. (Norton: New York, 1991) p.51-2.

[viii] Babcock, W.H. “The Eastern Shore of Maryland”. Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine. August 1888. p. 273.

[ix] Helen C. Rountree and David E. Davidson. Eastern Shore Indians of Virginia and Maryland. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997) p. 3.

[x]The Weather Channel. “Monthly Averages for Salisbury Maryland”. http://www.weather.com/weather/climatology/monthly/21801 11 May 2004.

[xi] Paul F. Gemmill. “The Agriculture of the Eastern Shore Country.” Economic Geography. Vol. 2, no. 2 (Apr. 1926) p. 199.

[xii] Anonymous. “Delaware Fruit Crops” New York Times (April 11, 1874): p. 4.

[xiii] Gemmill p. 199.

[xiv] Gemmill p. 199.

[xv] Rountree and Davidson p. 84-5.

[xvi] Rountree and Davidson p. 88.

[xvii] Henry M. Miller. “Transforming a ‘Splendid and Delightsome Land’: Colonists and Ecological Change in the Chesapeake 1607-1820.” Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences. Vol. 76. 3. (Sept. 1986): p. 174.

[xviii] Lois Green Carr. “Diversification in the Colonial Chesapeake: Somerset County, in Comparative Perspective.” Colonial Chesapeake Society. (Chapel Hill:University of North Carolina Press, 1988) p, 344.

[xix] Carr p. 348-9.

[xx] Carr p. 357.

[xxi] Carr p. 357.

[xxii] Carr, p. 362.

[xxiii] Carr, p. 372.

[xxiv] 1850 US Census. United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 11 May 2004.

[xxv]1850 US Census United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 20 April 2004.

[xxvi]1860 US Census United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 20 April 2004.

[xxvii] 1870 US Census United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 20 April 2004.

[xxviii] 1880 US Census United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 20 April 2004.

[xxix] 1850 and 1860 US Census United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 20 April 2004.

[xxx] 1870 and 1880 US Census United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 20 April 2004.

[xxxi] 1850 US Census US Census United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 20 April 2004.

[xxxii] 1860 and 1870 US Census United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 20 April 2004.

[xxxiii] 1880 US Census United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 20 April 2004.

[xxxiv] 1880 US Census United States Census Bureau, University of Virginia Library. http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/censusbin/census/cen.pl?year=880. 20 April 2004.

[xxxv] Cooper, Richard W. Salisbury In Times Gone By. (Gateway: Baltimore, 1991) p. 144.

[xxxvi] Cooper, p. 144.

[xxxvii] R.L. Hoxie. Lieut. Col. Corps of Engineers. U.S. Congress House. Preliminary Examination of Wicomico River, Maryland, From its Mouth to Salisbury. 59th Cong. 1st Sess., 1906. H.R. 908.

[xxxviii] D. W. Lockwood, Lieut. Col., Corps of Engineers, U.S. Congress House. Preliminary Examination of Wicomico River, Maryland, From its Mouth to Salisbury. 59th Cong. 1st Sess., 1906. H.R. 908.

[xxxix] Truitt, Charles J. Historic Salisbury Maryland. (Country Life:Garden City, 1932) p. 89.