Segregation Lingers in Wicomico County

Brooke Murphy

Despite what some may think, growing up on the Eastern Shore has been much like growing up in any small town. While Wicomico County may seem “behind the times,” it is not ignorant of change. This small portion of Maryland changes along with the rest of the world, perhaps at a slower pace, perhaps at our own pace. Nevertheless, this area has changed and accommodated every new era. Growing up, however, I was ignorant of the relation between my hometown and the rest of the world. I was fortunate to grow up on the Wicomico River, with Pemberton Park as my backyard, and I blissfully ventured through my childhood without a care. I happily accepted my world: my friends, my education, my neighborhood, and the entire town of Salisbury. I, like most children, rarely questioned my upbringing. Recently, however, I removed my blinders, and I began to reconsider my experience. Noticing the current residential segregation on the Wicomico River, I wondered how long this had been an overlooked stain of Wicomico County. The past and present geography of Wicomico County unmistakably exposes the relationships between the people and their values of the land along the river.

Segregation in Wicomico

County?

In 2001, the population of Wicomico County was 84,644 people: 72.6% were white, and 23.3% were black. [1] These figures were relatively unchanged from 1963, when the population was 53,060: 78.2% white and 21.8% black. [2] Accordingly, the geographical relationship between these two races similarly remains. In Wicomico County, this proof is often ignored, mainly because of our border-state status. Ask any local whether the Eastern Shore of Maryland is considered the North or the South, and the answer will be consistently different. Truthfully, the town of Salisbury is about twenty miles south of the Mason Dixon line; logistically, Salisbury is part of the South. Certainly Northerners consider us Southern, and our mildly warm weather supports this estimation. However, citizens are constantly disputing our union with the North or the South. For example, a white resident, Hamilton Fox claims that we may be South according to the books, but our existence is quite Northern. [3] On the other hand, an African American native of Wetipquin, (a small rural town on the outskirts of Wicomico County closer to the Nanticoke River), says that Wicomico County is socially Southern. [4] Although different measures of residential segregation occurs in both the North and the South, understanding Salisbury’s connection with either of these helps to more clearly understand local race relations.

Throughout geographical history, social and spatial distances co-existed in a conditional relationship. Where social distance was significantly large, there was typically less spatial separation between whites and blacks. The inverse relationship between social and spatial distance dates back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when slavery was at its peak in many colonies in North America. In the South, there was distinct social distance between plantation owners and slaves: the two small societies could live within close proximity of one another without the white society feeling threatened. On the contrary, in the North where social distance was not as clearly defined, whites felt the need to further spatially separate themselves from blacks. [5] Interestingly enough, during the Civil War, the population of Wicomico County was divided between sympathizers for the North and South. [6] Slaves in Wicomico County most likely lived on the plantations with their owners; their close proximity was allowed by the great social distance between them. After the Civil War, when social distance slowly lessened, Wicomico County whites felt the need to spatially separate themselves from blacks. In response, four primarily black neighborhoods, (Cuba, [developed in 1909], Georgetown, Jersey and California), were created for blacks on undesirable land close to the Wicomico River and its tributaries. [7] Thereafter, Wicomico County mimicked national trends in the way of residential segregation, and it has silently and unquestionably been maintained since then. To this point, race relations, in particular residential segregation, have not been addressed. Citizen’s ignorance of these issues throughout Wicomico Count’s history and their present unawareness of geographical segregation are evidence of the socially engrained social inequities of Wicomico County.

This recent map shows the

predominantly black neighborhoods in Wicomico County, and the white

neighborhood of New Town.. Note Johnson Pond and the Lower Wicomico River

While driving through the small town of Salisbury, I am intrigued by the human geography that seems so natural that it is “almost invisible.” [8] Looking closer, I become aware of the distinct segregation adjacent to both sides of Johnson Pond, a dammed branch of the Wicomico River located between Lake Street and the waterfront property of New Town. On the New Town side of the pond, upper middle class houses line the waterfront bluffs, a location which has become desirable over the past forty years. Their newly restored and freshly painted homes are close in proximity to one another, but separated and individualized by plush green lawns and closely manicured landscapes. Driving west, I cross a railroad track and observe a different world.

The

traffic of Isabella Street crosses the railroad tracks that separate New Town

and

To my left, I catch a glimpse of the industry at the port of the Wicomico River. I immediately survey the barges resting in the unclean water, depositing gravel and other profitable goods to local distributors. Approaching Lake Street, I see debris of demolished buildings, empty and unused warehouses, and seemingly unkempt streets. Standing from a vantage point directly across from the fine homes of New Town, this “other” waterfront property, (apparently undesirable for the White middle class), is uniformly bordered with smaller, low-income homes and nonexistent or short and unattractive yards. This is Sunset Heights, or the Westside.

Rows of uniform, low-income housing marks the heart of the Westside.

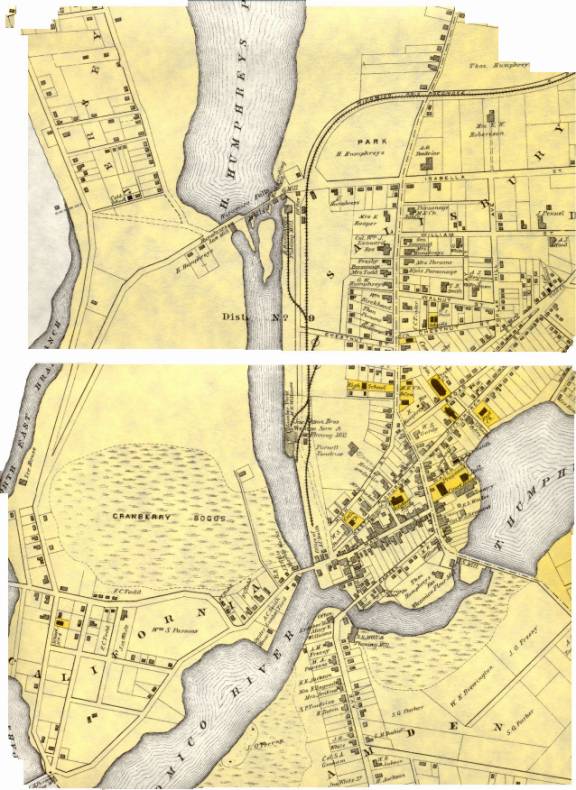

These geographical descriptions are even more interesting when compared

to historical maps. Below is a

1870 map of Salisbury, obviously prior to the drainage of T. Humphrey’s Lake

and the creation of the major roadways. One

sees that the Westside is located in Jersey in the 1870s, as well as in what

used to be cranberry bogs, or swamps. At

the time this map was created, the railroads, particularly the Wicomico and

Pocomoke Railroad, and the Wicomico River were the main industrial trading

areas; according to the map, these neighborhoods would have been the closest

communities to the dirtiest, smelliest, and loudest commercial locations of

Wicomico County. Notice also that

black residences are unnamed according to this map, while dominant white

residences in Jersey are marked with significant attention. Over time, these sizeable white residences will remain, be

recorded, and some restored like Poplar Hill Mansion. Meanwhile, no “historical houses” remain in the Westside.

The homes and shacks of black residences will be erased from time;

unnoted on maps and in history books, and forgotten in the minds of Wicomico

County citizens.

This 1870 map of Salisbury reveals much about the historical residential, and social, separation - note particularly where the swampy low ground is located in relation to the higher (New Town) bluffs. Note also where the railroads and docks create an industrial corridor.

These geographic phenomena, which persist unquestioned by residents and travelers, provide abundant “patterns and clues waiting to be organized,” particularly regarding residential segregation. [9] In particular, the train tracks, highways and Wicomico River form boundaries for this, (and other), black neighborhoods in Wicomico County. First, the Westside is clearly separated from this section of New Town by the train tracks and Johnson Lake. Historically, “African Americans swam on one side of Johnson Lake, the local public swimming area, while Whites swam on the other side.” [10]

New Town waterfront property on Johnson Lake, from

the Westside banks.

The

Salisbury Police Station on Route 50 between two predominantly black

neighborhoods.

Sink

signs: dirt piles, billboards, abandoned warehouses, and empty parking lots.

Geography and Language

These externally inferior neighborhoods have been, and continue to be, referred to as the ghettos of Salisbury. There are three components in the formation of ghettos. First, the dominant socioeconomic class differentiate themselves from a group of “others.” Next, the “others” are associated with a particular place. Finally, this selected area “becomes undesirable,” and the formation of the ghetto is complete. [16] The use of the word “ghetto” may seem severe being applied to the low-income, residential areas in Salisbury, especially compared to the ghettos and slums of larger cities, such as those in New York City and Baltimore. However, these areas are labeled relative to their surrounding communities: in comparison to other neighborhoods in Wicomico County, the areas labeled “ghettos” are different socially, economically, and racially. The historical origin of the term means just that.

The term "ghetto" often reminds us of the Warsaw ghetto, a symbol of Jewish history; however, its derivation in the United States is more closely associated with the influx of immigrants into cities. Immigrants from various backgrounds, nationalities and religions flocked together in the center of cities, where they would find others like them, as well as opportunities for jobs, education and upward mobility. [17] These ghetto experiences were often trying, even desolate, but the conditions were endurable because they were thought to be temporary. These old ghettos contrast with new black ghettos in that the presence of the latter has become a permanent and entrapping “American institution.” [18] The nature of the new ghetto is quite different from that of its origin, and the use of the word reflects racial stereotypes and assumptions about blacks. “Blighted residences” is an evolutionary phrase referring to the areas that older residents still refer to as “ghettos,” but I choose not to soften the polarization between ghettos and suburbs by using so-called politically and socially correct language.

Black ghettos are also associated with certain neighborhood names, and while these names change over time, the allusions to the black ghetto do not. The dominantly black communities in Wicomico County have historically acquired names that faded in and out of different eras. Older neighborhoods have been substituted with new names, but the implications of these names remain in the minds of residents. For example, prior to the development of Route 13 in the 1930s, there were two black neighborhoods designated with the names Cuba and Georgetown. According to the records of many local historians, Cuba and Georgetown were menaces to police, and unattractive to the eye; one can infer that these were the ghettos of that era. The remains of these destroyed neighborhoods are now considered part of the Church Street Area. Also, California, a West Coast state, referred to the black district along the west side of the River. This area is now assigned the name Fitzwater, although many young white children refer to it as “brown town.” The black neighborhoods on the north side of Route 50 are presently referred to as the Westside, as they are located west of the Wicomico River. As many pop-culture rappers have signified, the Westside of many cities refers to the ghetto. Sunset Heights is the designated name for the neighborhoods west of Isabella Street. Jersey Heights, a newer and respectable residential area is located further north on Johnson Lake. Although the language referring to these locales has changed, the connotations associated with these areas have not. These references imply ghetto-like conditions and therefore many believe these so-called ghettos accommodate low-income blacks; this is not necessarily the truth.

Segregation Reflects Power Struggles

It is important to recognize that nationwide, people choose to live where they are comfortable and where there is a sense of sameness. Since the 1920s, “large numbers of Blacks [have] moved into districts that were retaining a racial as well as an economic stigma. The existence of black ghettos became justifications, in and of themselves, for continuing segregation.” [19] Individuals are more likely to live in locations with those of similar background, however many blacks are categorized as one class when they live in similar neighborhoods. Unfortunately, these neighborhoods are separated by seemingly natural divisions that silently confine black mobility. [20] The Wicomico River, the railroad tracks and the downtown industry that seem to be apparently harmless divisions, actually act as planned obstructions that inhibit movement and limit power. These buffers physically and socially isolate the residing black communities, therefore maintaining their residential status and horizontal economic mobility. Altogether, these natural and man-made obstructions and buffers make them socially, economically and politically powerless. Each time a black family moves into a designated black community, residential segregation is perpetuated. This reflects past and present social relationships in Wicomico County. The polarization between blacks and whites became especially apparent when the dominant class entirely relocated black communities.

Relocation Results from Highway “Progress”

The relocation of black neighborhoods has not always been the choice of the residents; on the contrary, throughout black residential history, relocation has been imposed by Wicomico County and the city of Salisbury. These instances occurred with the development of highways. While Salisbury had long depended on the railroad and the waterways for commerce, movement towards automobiles became a necessary reality for travel and business. The first highway development occurred during the 1930s when major roadways were becoming “the biggest things around.” [21] While these roadway advancements became necessities with heavier flows of traffic, population increases, and socioeconomic progress and development, highways in the town of Salisbury acquired the reputation of running through and destroying black neighborhoods.

Richard Cooper, a locally respected historian and engineer, refers to this highway expansion in his description of the creation of Route 13 in the 1930s: he specifically recalls the “factor” of a “sub-marginal residential area” that happened to fall in the way of the newly designed highway. [22] Cooper suggests that it might have been “extenuating circumstances” that the highway was to be built through Cuba and Georgetown; he also essentially states that the construction of the highway was an easy way to “clear out the residue of this problem area.” [23] He complains that the creation of the Route 13 bypass unfortunately left “remnants of ‘Cuba’ and ‘Georgetown,’” areas he claimed were well known to the local police department. [24] Nevertheless, as Cooper mentions, the creation of Route 50 in the 1950s would take care of the rest of these areas, “and Salisbury would once again come out ‘smelling like a rose.’” [25]

Georgetown and Cuba Revisited

The Maryland Public Information Network describes the neighborhoods of Cuba and Georgetown more intimately than Cooper, and offers a better understanding of the richness of these black communities. Together, these low-lying communities were found at the end of the slope of what is now New Town. Cuba, or “Cubie,” was located south of Georgetown, along Cathell and Water Streets and the alleys surrounding these streets. It was often referred to as “round the pond,” the pond being Humphrey’s Lake. The neighborhood consisted of mostly rented homes and several black-owned homes. [26] Linda Duyer explained that Cuba is remembered as slum-like; she further suggested that some of the homes in Cuba were made from the bricks of burnt-down homes from the Salisbury fires of 1860 and 1886. [27] This notion demonstrates the condition and value of the Cuba residences.

Its adjacent neighborhood, Georgetown, was a considerably respected black neighborhood prior to the development of Routes 13 and 50. Georgetown was not a string of poor black residences, as Cuba may be remembered; rather, it was a well-developed black community. Many residents owned their homes, and some owned their own businesses within the locale. The business section “included Bob Toulson’s tailor shop, James Steward Funeral Home, Joe Cornish’s Bicycle Shop” and several other stores. [28] In addition, three churches resided in the Georgetown area prior to the development of Routes 13 and 50. The St. Paul AME Church maintained several locations before being built in Georgetown in 1942. Georgetown was also the location for the First Colored Baptist Missionary Church. Lastly, Georgetown was the home of John Wesley Methodist Episcopal Church, which, in 1837, “was purchased by a group of free blacks from a white family to build a house of worship and a school.” [29] The John Wesley Church was the only church spared in the development of the two major highways; now the church is restored as the Charles H. Chipman Cultural Center, a growing foundation honoring the African American culture and history of Wicomico County. [30]

Disgruntled Jersey Heights

Residents

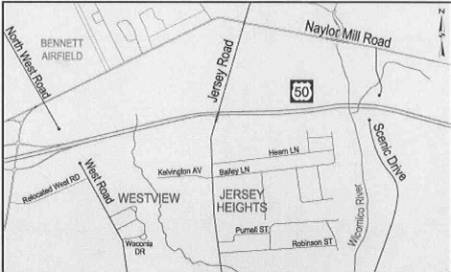

More recently, the creation of the Route 50 bypass created major concerns in the primarily black middle-class community, Jersey Heights. Jersey Heights can be found on the 1870 map to the East of the North East Branch and to the West of Humphrey’s Lake. The North East Branch has since been renamed the Coty Cox Branch, and Jersey Heights is now designated between Jersey Road and the Wicomico River. In 1999 the Jersey Heights Neighborhood Association challenged the construction of the new Route 50 bypass close to their residential area. While they recognized the need for the bypass, (due to the heavy traffic destined for the Ocean City Resort), the Association brought seven suits against the state and federal highway officials.

Phase 2 of Route 50 bypass construction: bridges over

Jersey Road and Wicomico River,

Road improvements on Jersey Road of Jersey Heights.

Public Housing

In the mid-twentieth century, when movement towards integration was affecting every town in America, Wicomico County officials attempted to do their part to alleviate racial friction. While towns and cities across the country experienced sit-ins and demonstrations, the mayor of Wicomico County created a Bi-Racial Commission to help ease racial tensions. The Bi-Racial Commission took preventative measures by lobbying local businesses to open their service base to blacks. [35] In addition, within the first few years of its existence, the Bi-Racial Commission urged the city and county councils to address the housing situations of the black community.

Corddry describes this controversy in a chapter of Wicomico County History devoted to “Race Relations” in Wicomico County. He writes that although many citizens in Wicomico County were against public housing, the project was needed to accommodate housing for low-income families. During the peak of this commission’s work, Hamilton P. Fox specifically clarified, “ ‘The Negro is often paying as much per month for substandard housing in neighborhoods without sanitary facilities as a white family in middle-class sections of Salisbury.’” [36] This is typical of sinks in that they are usually the last places to obtain housing codes and substantial facilities. In response, a new housing authority was selected and a maximum three-year plan was made for the planning and development of public housing. In the meantime, the Authority “leased satisfactory existing houses,” for 25% of the residents’ income. [37] Milford W. Twilley built affordable public housing in an area “convenient to either black or white applicants;” the housing was completed in 1968 as the Booth Street Townhouses, located in the heart of the Westside. [38]

A quiet afternoon at the Booth Street Townhouses.

Ignorance Perpetuates Segregation

We would like to believe that these instances of intentional residential separation were important decisions made under “extenuating circumstances,” as Richard Cooper suggests. However, with the exception of the success of the Jersey Heights Neighborhood Association in the last three years, the voices of the black residents have long been ignored. These displacements, as well as the current condition of some neighborhoods, show the ongoing devaluation of Black communities and the perpetual white dominance in Wicomico County. Despite the excuse of older generations who claim that things “have always been that way,” residential segregation did not just appear one day for no apparent reason. Historically, cities and towns were organized in a segregated manner to ensure that the “other” class remained stagnant and immobile, while the upper class maintained power, (and all that it derives from, i.e. money, political influence). Residential segregation is based on more than spatiality; it is fundamentally supported by social conventions and practices. [39]

One factor that perpetuates residential segregation in Salisbury is the white population’s unawareness of black communities. Take, for example, a lesson I learned from my contact from Wetipquin. During our interview, she popped me a question about my opinion of the location of the newest public middle school in Wicomico County, (Salisbury Middle School, located on Morris Street of Jersey Heights). Recent hearsay of disgruntled parents flashed through my mind, and I hesitantly replied that I didn’t think it was in the greatest section of town, (guessing from the look in her eyes that I would eat my words after this moral lesson). She calmly told me to take another look around this area the next time I was near the school, and then see what I thought. She suggested that many whites in Salisbury, (and all over the country), make assumptions about that which we know nothing. Sure enough, the next week I drove through the region of Salisbury Middle and was encountered with the truth of her statement.

Traveling along Lake Street, I passed through the Sunset Heights neighborhood. The area becomes more open and green, as Salisbury Middle School sits comfortably on an expansive grass lawn. Along the sparkling Morris Street, facing the school, quaint homes are graced by landscaped shrubs and trees, and many walks are lined with spring flowers. A vast wooded lot adorns the area north of the school, and Johnson Pond blocks the sounds of the highway along the east side, as do the neighborhoods to the south. My Wetipquin friend was correct in her predictions: locals categorize certain sections of town as “bad,” as places we wouldn’t want to send our children to school. Specifically, I grouped all black neighborhoods in the sink category, and automatically failed to recognize their potential.

Salisbury Middle School lies on a huge plot of grassy

land, with trees on most sides of the

Morris Street, with Salisbury Middle and many fin

Although my Wetipquin friend knew enough of Salisbury to teach me a lesson, she was glad to grow up outside of the hub of the Eastern Shore. In her rural community in Wetipquin, she fondly remembers wading in the clean Nanticoke river, fortunate for having grown up in a time when the waters were seemingly clean. Her father was a waterman, but also owned a small cash-crop farm, littered with cows and hens in the off-season. She claimed that she grew up on the right kind of food: she favors oysters and fish, proving that the river was a major resource for her family. Her family’s farm was amongst those of Polish, French, German, white and black “folks,” and she expressed that despite the diversity, there were few prejudiced feelings within her community. In fact, the neighbors were friends who looked out for one another’s children and borrowed baking goods when they ran out. [40] She implied that there is a significant difference between small farming communities and large towns. In her community, there was no need for spatial distance. While cities tend to alienate individuals into categories, (white/black, rich/poor), small communities allow for differences and are more accepting of social stratifications. As she pointed out, she was raised to believe in treating people as individuals. Early on, she recognized that contrarily, many white people of Salisbury treated other races as groups, and neglected to see people as individuals. [41] Her recollections imply that her congenial community was diverse and healthy; perhaps these qualities should be instilled in all neighborhoods in order to improve the way they are valued.

Efforts to Relieve Residential Segregation

Socialized injustices are embedded in our culture; consequently, residents, realtors and loaning companies need to make conscious efforts to aid, support, and empower long-neglected communities. The conditions of neighborhoods, and the way people refer to these places show how they value their communities and the land. One major contributor in the effort to value the relationship between land and people is the Salisbury Neighborhood Housing Service, Inc. (SNHS). This non-profit organization came into existence seven years ago, when the Wicomico County Bankers Group initiated an effort to lower the high-rent ratio in certain areas of Salisbury; the targeted neighborhoods are the Camden Avenue Area, the Church Street/Doverdale Area, and the Westside. They are devoted to offering “below-market loans and reduced closing costs” to those who wish to become homeowners, and they do so with the help of local public and private lenders. [42] There are no minimum or maximum income requirements, so SNHS has loan products for families of all incomes. They are not only “striving to increase home ownership rates but also to make the neighborhoods more economically diverse.” [43] Their motivation stems from the theory that over time neighborhoods with high rental properties deteriorate. The organization supports the idea that with home-ownership comes pride, and consequently neighborhoods are apt to have lower crime rates, safer streets and a sense of community. Their mission statement is a declaration not only of commitment to create more stable and safe communities, but also to empower homeowners: “To renew pride, restore confidence, promote reinvestment and revitalize neighborhoods.” [44]

Thus far, SNHS has made significant strides in accomplishing their mission. Their milestones include being chosen as a Pilot site for the State of Maryland Live Near Your Work Program (LNYW), a program developed as part of Governor Paris Glendening’s “Smart Growth” initiative. In an effort to fortify neighborhoods, the LNYW offers a $3,000 grant to potential homeowners who opt to live closer to their work. [45] Implied advantages to this program are that homeowners will spend more time at home and in their neighborhoods, and less time commuting. An environmental advantage of the LNYW means a shorter commute to work resulting in less automobile pollution. An additional accomplishment of the SNHS is its designation as the only Community Development Financial Institution on Delmarva. [46] Moreover, SNHS is one of 22 sites across the country associated with the Financial Fitness Program that organizes workshops to encourage wise and healthy money management. Participants interactively learn about budgets, spending choices, credit, consumer skills, bank accounts, and predatory lending. [47] Most importantly, in an area where 70% of the residences are rental properties, the SNHS has helped to increase home ownership, provided educational services, and improved the quality and respectability of the three target areas.

Cheryl M. Meadows, Executive Director of SNHS offered her own personal statement concerning the organization: “Our goal is to create neighborhoods that are both economically and culturally diverse. It is important to us to offer not only the lending products but the educational services as well. We want to provide our customers with attractive loan products and with the knowledge and skills they need to be homeowners.” [48] Meadows suggested that the success of SNHS is revealed through the following statistical progress. First, 73% of all first mortgages were made to first-time homeowners, 30% to minorities, and 36% to female heads of household. Furthermore, 40% of loans were made to families at or below 80% of area median income, and 30% of the people have a mortgage payment less than their previous rent payment. [49] SHNS is making it easier for low-income individuals and families to own homes, encouraging more respect for the land on which they live, and for the residing citizens.

Magnitude of Future Awareness

Considering the inevitable expansion of the white, upper-middle class developments outside the city limits, I fear that the black minority will not be able to socially compete with the dominant white culture because of the residential segregation in Wicomico County. SHNS is making it easier for low-income families to own homes, yet their progress is leaning towards gentrification. They are increasing the diversity of these neighborhoods by bringing in 70% white homeowners; however, where are the previous renters moving? Are black families being encouraged to move deeper into the pockets of the Westside? Furthermore, people’s new desire for waterfront property is outweighing earlier attitudes against it. The upper-middle class craves the cool reflection of Loblolly trees and Great Blue Herons surfing along the ebbs of the Wicomico River. What will happen to the sinks along the Wicomico River and Johnson Pond when hungry developers come their way looking to devour waterfront property? Already, Brew River Restaurant and Bar has established itself along Fitzwater Street, and it boasts of its deck and beautiful sunsets. Chesapeake Pottery has created its own cultural ambiance across the street, and the Salisbury Marina grows each year. How far will the dominant white population push its way up into the sinks of the Westside?

Brew River

on the downtown harbor; deck parties signify the value of waterfront

entertainment.

The awareness of residential segregation, in Wicomico County and other communities, is vital. First, it is imperative that individuals become aware of their surroundings: we are not eternally children, and therefore cannot be eternally naďve to the makeup of our environment. If black and white residents become aware of residential segregation, it will give them the opportunity to question their communities and recognize the unnecessary inequalities; upon recognition, they will be more likely to make changes. Awareness also comes from more closely examining the patterns of Wicomico County in relation to history. The history commonly taught in our schools is normally accepted as truth; it is the research beneath accepted history that reveals hidden patterns that exist today. The maintenance of residential segregation has proven to be a significant manifestation of social trends across the United States. While residential segregation is preserved in the urban and rural areas of both the North and the South, its existence is too widely ignored or accepted. The geographical changes that occur along the Wicomico River are rich with meaning. Roderick Nash states, “So nature is not only a document revealing past thought and action but also a slate upon which the present outlines the kind of world it bequeaths to the future.” [50] We have seen the history of residential segregation along the Wicomico River; in order to instill hope, we must be attentive to present societal ills and begin to paint a more promising future along our valued river’s edge.

What

does the future hold for the Fitzwater waterfront property?

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, County and City Data Book: A Statistical Abstract Supplement (Washington D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2001).

[2] Division of Statistical Research and Records, Maryland State Department of Health, Final Vital Statistical Tables: Maryland, 1963 (Maryland: Maryland State Department of Health, 1964), 1.

[3] Hamilton P. Fox, interview by author, tape recording, Salisbury, Md., 15 March 2002.

[4] Anonymous, interview by author, note recording, Salisbury, Md., 21 March 2002.

[5] George A. Davis and O. Fred Donaldson, Blacks in the United States: A Geographic Perspective (USA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1975), 110.

[6] George H. Corddry, Wicomico County History (Salisbury: Peninsula Press, 1981), 16.

[7] The Jersey Heights Neighborhood Association, Complaint: Preliminary Statement, 22.

[8] Grady Clay, Close-Up: How to Read the American City, (Chicago: Chicago Press, 1980), 145.

[9] Clay, 11.

[10] The Jersey Heights Neighborhood Association, 31.

[11] Davis and Donaldson, 130.

[12] Clay, 143.

[13] Clay, 145.

[14] Linda Duyer, interview by author, telephone conversation/ note recording, Salisbury, Md., 24 April 2002.

[15] Clay, 143.

[16] Davis and Donaldson, 129.

[17] Richard C. Wade, “The Enduring Ghetto,” Journal of Urban History, Vol.17 (1990), 5.

[18] Wade, 7.

[19] Davis and Donaldson, 129.

[20] Davis and Donaldson, 130.

[21] Clay, 91.

[22] Richard W. Cooper, Salisbury in Times Gone By. (Baltimore: Gateway Press, 1991), 263.

[23] Cooper, 263-264.

[24] Cooper, 263.

[25] Cooper, 264.

[26] SAILOR: Maryland’s Public Information Network, “Inventory of African American Historical and Cultural Resources: Wicomico County” (Maryland Commission on African American History and Culture, 2002), http://www.sailor.lib.md.us/docs/af_am/wico.html, 7.

[27] Linda Duyer interview.

[28] SAILOR, 8.

[29] SAILOR, 3.

[30] SAILOR, 3, 8, and 9.

[31] Linda Duyer.

[32] Freda, 8.

[33] Charles Whittington, interview by author, note recording, Salisbury, Md., 28 April 2002.

[34] Charles Whittington interview.

[35] Hamilton P. Fox interview.

[36] Corddry, 66.

[37] Corddry, 66.

[38] Corrdy, 66-67.

[39] Davis and Donaldson, 109.

[40] Anonymous interview.

[41] Anonymous interview.

[42] Salisbury Neighborhood Housing Service, Inc., SNHS Pamphlet (Salisbury, Md: Neighborworks, 2002), 1.

[43] Cheryl Meadows, interview by author, via email, Salisbury, Md., 25 April 2002.

[44] SNHS, 1.

[45] The Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development, Live Near Your Work Pamphlet (Baltimore, Md: Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development, 2002), 1.

[46] SNHS, 6.

[47] Salisbury Neighborhood Housing Service, “Are you tired of constant money troubles: Financial Fitness Workshops” (Salisbury, Md.: Salisbury Neighborhood Housing Service, 2002), 2.

[48] Cheryl Meadows interview.

[49] Cheryl Meadows interview.

[50] Roderick Nash, American Environmentalism: Readings in Conservation History. 3rd ed. (New York City: McGraw Hill, 1990), 2.